Historically, philosophy and science started out as one body of knowledge. Over time, scientists distanced themselves from philosophy, arguing that it lacked the rigor of the scientific method. Philosophy was then slowly discredited, and considered speculation akin to theology in the eyes of many academics.

As science made remarkable progress towards deciphering the natural world, it was only inevitable that the study of humanity, once a fundamental affair of philosophers, would be studied “objectively” through scientific lenses [1]. Since then, other ways of inquiring about human nature were seen as less valid.

New fields emerged from this rupture between science and philosophy, an ambiguous group referred to as “humanities”, “social sciences” or “liberal arts”, which were then seen as more credible than the less fashionable philosophical methods. These methods would focus on “empiricism”, or verifiable facts about humanity, rather than “mere speculation”, and they generally fall into three categories.

First, the “nomothetic” [1] approach (from nomos, which can be understood as “law”), attempts to figure out the universal laws that constitute human nature, and aligns itself with the methods of the natural sciences. With this goal in mind, realms such as experimental psychology, economics, sociology, and political science were born. Those who follow this method imagine that the laws they develop apply to all of humanity, as physical laws apply to all of nature.

The second approach, the “idiographic” [1] (from idio, meaning “own”, “personal”, or “distinct”, and graphḗ, meaning “writing”, “drawing”, and “description”), relies on methods closer to arts and literature, and includes fields such as anthropology and history. This approach describes humanity as contingent, or subject to very particular circumstances. There is always a culture, perhaps some tribe somewhere, or a different historical time period, with a completely distinct way of living and thinking compared to what is presented as universal. The idiographic approach leads to the suspicion that anything that portrays itself as universal in the study of humanity is likely a social construction that cannot see its own origins.

As these two approaches gained traction, they isolated and specialized until they became incompatible. Universities taught subjects in compartmentalized ways, where different branches presented themselves in direct opposition to each other, making it difficult to create connections amongst different fields. This created conditions where humans could be explained either in a nomothetic way, or they could be seen through idiographic lenses.

However, a third approach arrived later to reconcile the apparently incompatible branches of knowledge about humans, proposing a viewpoint that accepted humans as complex beings. The word “complexity” comes from the Latin “complexus”, which means “woven” – many elements woven together, interacting jointly constitute a complex system.

Humans were then considered to be complex as they are constituted by many layers of biological and environmental elements. Through this perspective, they aren’t just historical, economical, psychological, sociological, or biological, etc. They are the end result of a conjunction of elements interacting in all these seemingly disconnected levels, an articulation of systems [2]. It was also discovered that slight changes in a complex system’s conditions can produce dramatic and unpredictable changes in its behavior over time [3].

Those who follow this complex, idio-nomothetic approach tend to conclude their research by saying the once exciting, but now repetitive, “both biological and environmental conditions play a role in “X”, “Y”, or “Z”, but we can’t determine exactly to what extent”. With an immense quantity of elements to deal with when it comes to the study of humans, researchers are frequently unable to isolate causal relations; “this causes that” can no longer be said, instead, they find themselves constrained to “this is associated with that”. Thus, guesstimates are thrown all over the place about what causes what.

This complex approach points to the idea, (as initial conditions for experimentation are different from study to study, and slight changes end up seriously altering the behavior of systems), that any attempts to research anything about the human mind and behavior that isn’t completely banal gets slippery. This is why academics are unable to replicate a high percentage of psychological experiments, leading to the so-called “replicability crisis”.

When it comes to the study of the mind and human behavior, it often appears as if investigators have managed to do research “objectively”. However, as these different approaches, with their pros and cons, create depictions of what humans are like, they inevitably establish perspectives that end up, in turn, paradoxically shaping people as a whole. In other words, they become “self-fulfilling prophecies”.

This is similar to the analysis of the philosopher Fauerbach [4], who claims that humans create God, and, eventually, a process of separation occurs where humans forget that they have created God, and then, God creates them. Thus, the idea of God rules society. Entire civilizations, including the West, revolve around this process.

The Hindu tradition hints at this in the Upanishads where it is said that: “We are like the spider. We weave our life and then move along in it. We are like the dreamer who dreams and then lives in the dream” [5].

In recent years, two particular branches of knowledge about humanity have become more popular, to the point where it seems as if they’re eclipsing other ways of making sense of mankind. Psychology and psychiatry, which largely rely on nomothetic methods, are expanding to the point that people categorize themselves based on psychological tests. Individuals are now quick to introduce themselves or their children as “gifted”, “ADHD”, “dyslexic”, etc. What is behind their popularity?

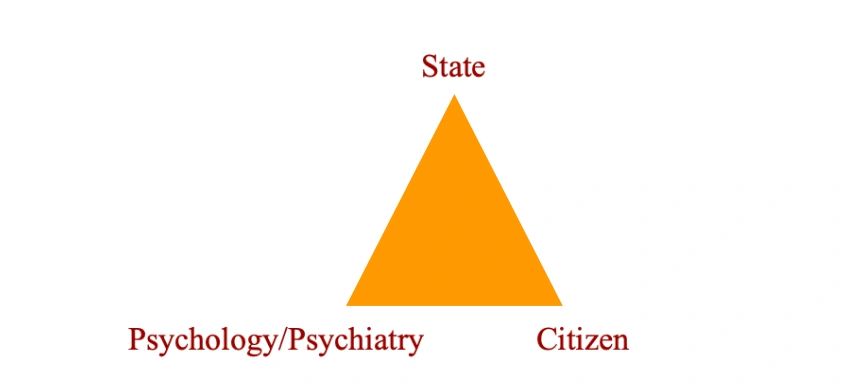

To achieve a better understanding of this situation, it is necessary to break down, on a societal level, the role of the potential players at hand. At first glance, it seems as if only psychologists/psychiatrists and patients are benefiting from the growth of these fields, however, an analysis would be incomplete without looking at the role of the State, a central figure who allows this whole process to occur. As the State is largely who funds academic research [6], and one of the largest employers of psychologists and psychiatrists [7][8], it must strongly benefit from nomothetic psychological/psychiatric methods.

As legitimacy regarding the study of human affairs shifts away from philosophy and towards scientific approaches, the contemporary State – which itself was built upon philosophical constructions – needs to employ scientific narratives to validate its actions. Psychological testing is an easy way for the State to objectify morality; and make it seem healthy. For example, only the criminal that passes certain tests might get out of prison, and a student can be diagnosed with maladies to make its educational model seem natural.

This allows the State to stop behaving in the style of a shameful executioner, and instead be seen as a “virtuous curer” [9] while forcing its citizens to behave in a certain way. The State gets to defer to “objective” psychologists/psychiatrists to make its system seem just.

Additionally, the State attempts to use psychology to find ever more precise techniques of control over its citizens. Psychology and psychiatry promote the resolution of in-group conflicts through psychotherapeutic and communication techniques, promising to reduce the burden on the legal system. Problems that might actually be collective are individualized, making people less likely to protest as a group. This seeks to create a more organized, standardized, and uniform society, ensuring a nation can compete more effortlessly on the global stage.

The psychiatrists/psychologists get to adopt a role akin to a priest, a privileged position in society, while obtaining some degree of power over the population. The more accurate their knowledge seems, the more universal and nomothetic, the more it is sought for. This makes psychology increasingly widespread, to the point where it objectifies as many elements of the law as possible. Psychiatrists and psychologists are, therefore, incentivized to create ever more disorders and categories, to assign them to more people, and to administer more tests. These professionals gain from creating theories, tests, and entities that they don’t fully understand, as long as the State is willing to use them. Thus, psychiatrists and psychologists gain from pretending to know more than they actually do. They get to exert a certain power that bypasses the legislative branch, while obtaining profits from pharmaceutical companies (another player that obtains immense dividends from this whole process).

As tradition is stripped away from contemporary society, and rituals are displaced from their role [10], individuals increasingly rely on psychological and psychiatric discourses to make sense of their lives. Psychological tests are seen as universal, objective assessments, unlike religion and ritual which seem tied to culture, and, therefore, blatantly false in the era of nomothetic scientific reasoning. Testing is then more sought for, in all areas of life; the entire narratives people tell themselves about their lives increasingly depend on what the psychologist/psychiatrist says. Suddenly, in order to obtain social benefits from the State, people have to subject themselves to ever more psychological/psychiatric examination as one of the few valid ways to get legal rights in a labor, educational, or even familial environment.

The reinforcement from these different players increases their relationary strength, forming a mutually benefiting bond which, in turn, cements the popularity and narratives of psychology and psychiatry. On the other hand, the idiographic approaches of anthropology or history are heard less often, giving rise to a psychologized subjectivity.

For example, US federal research funding for psychology was about $3.3 billion in 2020, while for anthropology, it was about $19 million in the same year [11]. This is a 17,368% difference. The National Science Foundation had a yearly budget of $9.87 billion in 2023 [12], while the National Endowment for the Humanities had a budget of $106.87 million [13], which is a 9,236% difference. In order to maintain funding, psychology must prove its practicality. It is encouraged as much as possible to stress itself as a science that offers nomothetic solutions to the government and members of the public.

Intelligence research is one of the hottest topics in psychology, and many claim to have found significant, universal, and objective results. It offers an interesting setting to understand how claims that benefit the State can get amplified before they are well understood.

On intelligence and its measurement

In the view of Socratic thought, humans are condemned to an imperfect world that will never live up to the ideal plane of concepts. Ever since Socrates, the West has been characterized by an eternal “the grass is always greener on the other side of the fence” view of the world. This is a crucial point for understanding Western culture. Things could always be better than they are, if only humans let go of their animalistic nature, and align themselves with reason. This has led to seeing abstract reason as more real than humans themselves in many circumstances.

The philosopher Ortega y Gasset [14], commented about the flawed human world, in the view of Socratic thought:

“The visible and tangible things change non-stop, they appear and then they are consumed… What is white darkens, water evaporates, man succumbs, what is bigger than something, becomes small compared to another thing. The same occurs in the interior world of men: desires change and contradict each other; when pain is reduced, it becomes pleasure; pleasure, with repetition, produces pain. What surrounds us, doesn’t offer us a safe point to rest our minds, nor does what’s within us.”

While on the other side, according to him, in the ideal plane:

“The pure concepts constitute a class of immutable beings, perfect, exact. The idea of whiteness, doesn’t contain any stain; movement could never become stillness; one is invariably one, in the same way that two is always two. These concepts enter in relations one with another without ever disturbing the other. Bigness inexorably repels smallness… The virtuous man is always more or less vicious; but Virtue is exempted of Vice. The pure concepts are, therefore, clearer, unequivocal, more resistant than the things that can be found around us, and they behave according to exact and invariable laws.”

If one is to accept the position of Ortega, it follows that “intelligence” or “smartness”, as a pure concept is unattainable, just as virtue is unattainable and any attempts of measuring virtue on the earthly plain, wouldn’t be feasible. This could explain why there is no earthly consensus on what is meant by intelligence in the first place. Subsequently, anything that can be measured in this regard, is already a limited perspective of what intelligence is; its universality is broken.

However, if one isn’t satisfied with this perspective, and accepts that intelligence is indeed of this earth, and therefore, assumes that intelligence can be measured, what would be the challenges at hand?

Intelligence testing in contemporary times consists of providing a series of questions that are cataloged as correct or incorrect based on their truthfulness. While the truth presents itself as a universal category, it can also be seen as a historically contingent category. Formulating this view, Foucault [15] argued that “each society has its regime of truth, its ‘general politics’ of truth: that is, the types of discourse which it accepts and makes function as true; the mechanisms and instances which enable one to distinguish true and false statements, the means by which each is sanctioned”.

Foucault [16] provides the example of 11th century Burgundy to showcase his point:

“In the old law of eleventh-century Burgundy, when a person was accused of murder, he could completely establish his innocence by gathering about him twelve witnesses who swore that he had not committed the murder. The oath was not based, for example, on the fact that they had seen the alleged victim alive, or on an alibi for the alleged murderer. To take an oath, to testify that an individual had not killed, one had to be a relative of the accused. One had to have social relations of kinship with him, which would vouch not for his innocence but for his social importance. This showed the solidarity that a particular individual could obtain, his weight, his influence, the importance of the group to which he belonged and of the persons ready to support him in a battle or a conflict. The proof of his innocence, the proof that he had not committed the act in question was by no means what the evidence of witnesses delivered.”

Similarly, another way of proving someone’s innocence was to “reply to that accusation with a certain number of formulas, affirming that he had not committed any murder or robbery. By uttering these formulas, he could fail or succeed. In certain cases, a person would utter the formula and lose not for having told a falsehood, or because it was proved that he had lied, but, rather, for not having uttered the formula in the correct way. A grammatical error, a word alteration would invalidate the formula, regardless of the truth of what one asserted. That only a verbal game was involved at the level of the test is confirmed by the fact that in the case of a minor, a woman, or a priest, the accused could be replaced by another person. This other person, who later in the history of law would become the attorney, would utter the formulas in place of the accused. If he made a mistake in uttering them, the person on whose behalf he spoke would lose the case.”

Some historians even argue that the whole idea of demonstrating a conclusion is historically contingent, and came from geometry [17]. Even today, many cultures prefer other mental tools, such as intuition and narration, and don’t put such a hard, “intellectual” dichotomy between fact and fiction [18].

Anthropologists argue that Western logic isn’t universal, which would make any universal IQ test difficult, to say the least. Evidently, ways of thought that seem completely integral to the West’s notions of intelligence, such as the ability to use mathematics, are completely foreign to some cultures. In the Amazon, the tribe of the Pirahas doesn’t have a word for a single number, nor any way of expressing quantification. Even after extensive classes from Westerners, adult members of the Piraha tribe were unable to understand basic mathematical concepts [19].

While it might seem as if logically categorizing information is a basic test of intelligence, ethnographers have found that it is wholly based on Westernized models of thought. In 1930, an ethnography was conducted on the people of Uzbek and Kirghiz from the remote regions of the Soviet Union. There were three groups sampled for the ethnography: uneducated peasants, somewhat educated farm workers, and well-educated students. The groups were asked to categorize objects by shapes and colors. Only the students were able to arrange the objects by the abstract categories of circle, square, triangle, etc. The others could name the objects, such as a bracelet or watch, but couldn’t arrange them by shape, because they represented completely distinct objects to the non-students. The same thing happened for colors, the non-students could name the objects, but couldn’t categorize them by color because the objects all seemed “too different”. The neuropsychologist Alexander Luria concluded from the ethnography that “the basic categories of human mental life can be understood as products of social history– they are subject to change when the basic forms of social practice are altered and thus are social in nature” [19].

Similarly, the tribe that lives in the regions of the planet where the weather changes dramatically through the seasons, might invent not just the canoe for crossing a lake during the summers but also the skates for the winters, while the tribe that lives in the hotter areas of the world, will only come up with the canoe [20]. Measuring the intelligence of both societies, one might be tempted to assume that the technological artifacts created by both tribes regardless of their environmental conditions, give an estimation of their intelligence. However, without taking into account the environment, one can’t see the full picture. While tests are administered to individuals in contemporary societies, the environment often presents itself as unpolluted, pristine, and unquestionable. As antiquated and unintelligent as some of these tribes might seem, they still don’t pose the very “smart” problem of destroying the world through atomic bombs.

Perhaps the writer Bierce [21] formulated this conundrum well, when he said that judging the wisdom of an act by its outcome, which is to say, by its result, is “immortal nonsense”, as the wisdom of an act is best judged by what the doer had in mind when he performed it.

Looking at the problem from the standpoint of complexity and the idio-nomothetic view, the biology of intelligence wouldn’t be separable from life experience. Therefore, an intelligence test of a few questions would be extremely limited, and it would fail at showing the myriad of causes behind what makes someone smart, that is, one´s genes, culture, upbringing, etc. A particular cause of intelligence could still never be found.

There are, however, those who, despite all of these limitations, insist on attempting to convince everyone that IQ testing has nomothetic validity. Let’s hear their claims.

It has been repeatedly found by psychologists that someone who does better in math is more likely to do better in reading. As another example, someone who is better at memorizing a set of numbers is more likely to be better at logic puzzles. Many psychologists claim that these results are caused by “general intelligence”. Or to put it in other words, everyone has something, a singular entity in their brains that causes them to do well on all these tasks. This entity is the same entity for everybody, and an IQ test claims to be able to measure how strong this entity is, and see how much of it someone has compared to everyone else. All humans have this same entity in varying degrees, and it has been given the name of “g-factor,” “g”, or “general intelligence” in psychology [22][23][24].

Psychologists and academics have suggested that this g might be someone’s “mental energy” [23], “mental power” [24], “central processing unit” [25] “system integrity” [26], “the efficiency of the brain’s wiring” [26][27], or “how conscious someone is” [28]. They imagine it is something foundational about the brain, or genes, as everyone has it [29][30]. This entity is also what modern IQ tests claim to be able to measure. In fact, this is the central claim of an IQ test [24]. However, they are yet to find the precise entity that they say is behind this [27].

What could be an approximation to this problem from an idiographic perspective? Let’s see an example:

A restaurant owner decides to create a “Disney Trivia” night in order to increase his revenue.

At the Disney Trivia night, the host asks a variety of questions that are supposed to measure all aspects of Disney knowledge. There are separate columns in the answer sheets for questions about Disney characters, Disney songs, and even a section titled, “What would this Disney character do?”, which is supposed to test Disney problem-solving abilities. The logic is infallible:

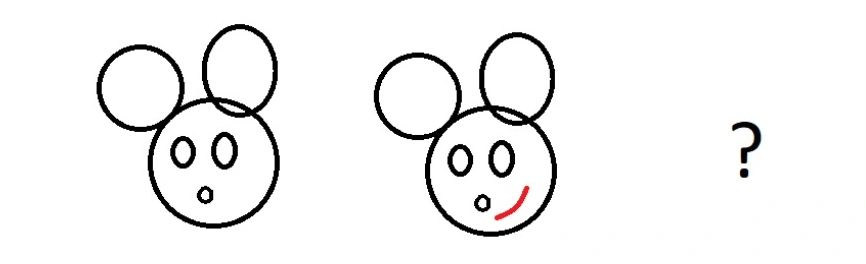

Everybody should know that after Mickey smiles, he always blinks, which has been done in thousands of episodes, prompting tests like the following:

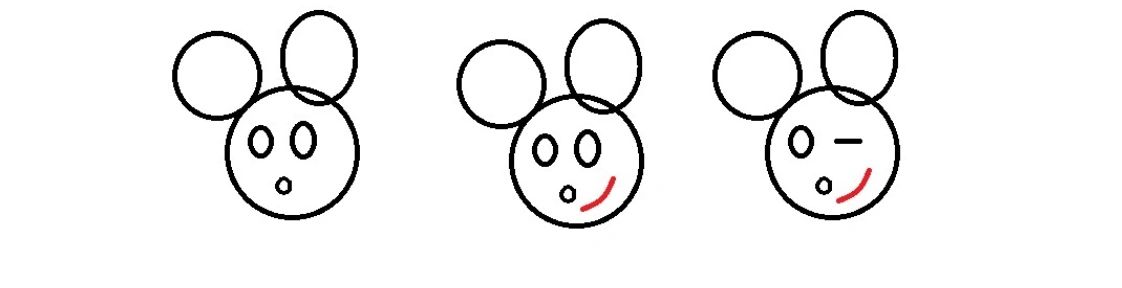

Which must be answered, in accordance with all Disney experts as:

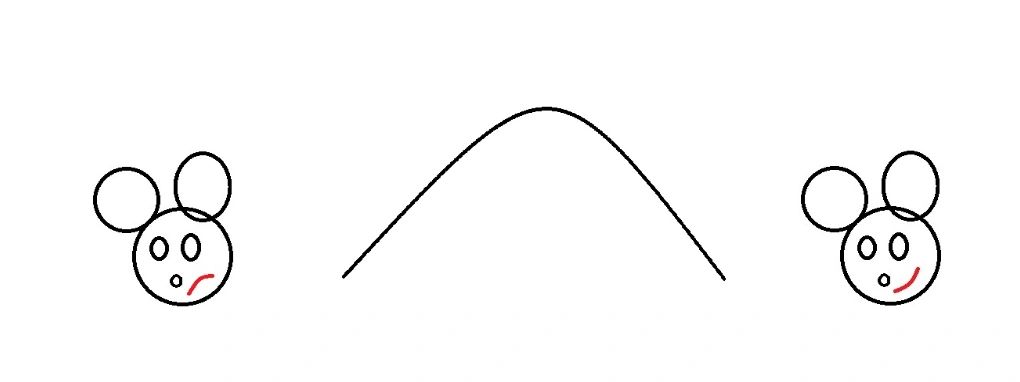

The restaurant owner soon notices that something quite odd is taking place. A distribution of the results looks special, it seems to follow a statistical bell curve:

Thus, the DQ (Disney Quotient) is born. Other restaurants start to take interest in hosting their own Disney Trivia nights, hoping to bring in more revenue. As more Disney Trivia is conducted, more data becomes available to the hosts.

Suddenly, all kinds of connections and correlations are found. One restaurant owner eventually realizes that if someone scores higher in the category “Disney songs”, they also tend to know more about “Disney movies”, and even on “Disney reasoning”. In fact, all the scores correlate!

This restaurateur thinks he discovered something important, even fundamental about the brain. He calls the unknown cause of these correlations the D-factor, and imagines that it must be a measure of someone’s “mental power”. This must be the case, he rationalizes, because if someone watches Toy Story over and over, he gets better at the Toy Story segment of the Trivia, but that doesn’t increase their overall Disney Trivia abilities. It doesn’t seem to increase the “mental power” that all true Disney champions tap into [31].

At a certain point, it was proposed that a true Disney fan should be able to answer any questions about any movie, even without seeing them in advance. Some people would argue that not seeing the movie in advance and getting the correct answer should be regarded as the purest form of “Disneyness”, the purest measure of the brain’s D-factor [32].

Little by little, as decades go by, Disney keeps growing and becoming ever more relevant to society. It is no longer just something nice to know; people now need to know about Disney, their DQ needs to be higher to work at the jobs that have the highest pay – the jobs that are inside Disney Itself [33].

As Disney develops better technology for their movies and rides, and replaces other companies, a high DQ becomes the only way to make a living [34]. To the surprise of many researchers, DQ was then able to predict one’s success in life, as no other instrument managed to do before [35].

It didn’t take long until countries that were never before exposed to Disney were having their DQ measured. People in Asia, who never saw the Universal Mouse, and couldn’t draw him blinking, were told they had an extremely low DQ, of which they should feel embarrassed. Not everybody lost hope, and some people dreamt of raising the DQ of this population, however, when the Asians couldn’t focus on the movies, they were deemed a lost cause.

While more funding is offered to fuel investigations, new researchers can’t seem to find any negatives about having a high D-factor. People with high D-factor levels tend to have more money, they are healthy, have more free time, and have plenty of other benefits.

Evidently, the next step is to figure out a genetic basis for the D-factor, hoping to engineer everyone to become better consumers of Disney. Others hope to create a new pill to magically make everyone’s DQ increase. More tests are conducted to see who can draw Disney ears faster, as their time reaction must mean something. Eventually, Disney Trivia answers are guarded and kept away from the public; only the highest Disney connoisseurs can create them, or are even qualified to speak about them.

Sometimes, Disney psychologists are faced with the question: “Is DQ solely biological?”, to which they answer “Some psychologists suspect that it is mostly biological, however, it is thought that some cultural elements are also at play”. When questioned: “Do we really need such a high DQ?”, they respond: “If someone offered you a pill that gave you 20 more points of DQ and another one that took 20 DQ points away from you, which one would you take?” [36].

Some journalists have attempted to show how DQ didn’t come out of nowhere, and that maybe it measures Disney’s influence rather than the mental power of the people who take the tests. Within the reports of these journalists it was written that the first Disney Trivia restauranter told everybody not to take trivia night too seriously, as it was just a way to make money on the side. But those journalists have been cataloged as crazy, with a low DQ themselves.

It seems as if, as Disney grows its influence all over the world, the DQ of the world increases. Some argue because of biology, some argue because of culture, some argue because of both. Who knows?

Some people wonder if perhaps DQ isn’t within the individual, but outside of it and environmental. Either way, Disney needs to keep running, one couldn’t envision a life without it anyways. Although anthropologists might ask if it is truly necessary for Tasmanians to learn about Cinderella, psychologists say they want everyone to have an opportunity to unlock their hidden D-factor potential.

Do we need the g-factor model?

IQ testing, and the idea that it measures some sort of foundational “mental energy” of the brain, has been extremely influential in Western societies [26]. But a “g-factor” or “general intelligence” that causes someone to do well on different academic tests might not actually exist [37], and from an idiographic standpoint, almost certainly doesn’t exist. There is simply no central building block of intelligence in the brain, especially one that exists in varying degrees for everyone, to be measured [38][39].

Astonishingly, ever since the original idea of the g-factor was created, researchers have known that a singular mental or brain entity isn’t required to explain why people who are better at one academic task tend to be better at others. The psychologist Charles Spearman claimed that these correlations suggested an underlying common factor, called “general intelligence”. Soon after, the educational psychologist Godfrey Thomson criticized this, and showed statistically that intelligence didn’t have to come from one central cause [40].

But Thomson is largely forgotten by history [41], as the theory that people have different, measurable levels of “mental power” or “efficiency of brain’s wiring” is such a powerful mechanism to justify differences in wealth, in addition to providing an easy way to compare one another, that it is still how IQ is largely sold to the public. The g-factor model of intelligence is also a convenient way to market IQ testing, as the Testing and Educational Support industry is worth $26.1 billion in 2023 in the US alone [42].

General intelligence doesn’t have explanatory power [43], and, therefore, IQ doesn’t measure what it claims to. Oftentimes, having a high IQ score is framed as an explanation as to why someone has high grades. But learning itself, through school, is what prepares someone to take an IQ test. For example, how well someone does on an IQ test increases through college education, and school in general [44]. Similarly, psychologists have repeatedly assumed that their IQ tests are culture-free and not based on Western education, only to find that their tools are contingently based on school [45]. This is also an explanation as to why, in the United States, the average IQ goes up about 3 points per decade as more people go to college, etc., which is called the Flynn Effect [46].

It follows that one can increase their IQ score through more years of school, if they chose to, as intelligence test scores can be improved through practice (they don’t recommend taking the test more than once every two years for this reason) [47]. Since a g-factor that causes someone to do better at tests than others doesn’t exist, practicing for an IQ test is not only valid, it is what everybody does through compulsory education. Additionally, it is becoming abundantly clear that the genetic and environmental factors that make up an intelligence score are extremely difficult, if not impossible, to calculate and separate [48][49].

When someone takes The Wechsler Intelligence Scale, one of the most common IQ tests, they are told they are getting an estimate of their “general intelligence”. However, researchers Han L. J. Van der Maas et. al argued in 2013 that “The mutualism model, an alternative for the g-factor model of intelligence, implies a formative measurement model in which “g” is an index variable without a causal role. If this model is accurate, the search for a genetic or brain instantiation of “g” is deemed useless. This also implies that the sum score of items of an intelligence test is just what it is: a weighted sum score.” They went so far as to title their article Intelligence is what the intelligence test measures. Seriously, and suggest that IQ tests should stop claiming to be an “intelligence measurement” [39].

Similarly, the intelligence psychologist Scott Barry Kaufman argues that “it’s quite likely that the cognitive skills that comprise IQ are positively correlated with each other in large part because society chose them to represent the foundation of education. In other words, we are the ones that laid the groundwork for them to be positively correlated as they are mutually developed in school” [50][51]. The 2007 paper A dynamical model of general intelligence suggests that it is the huge mass of published material on the general intelligence model itself that makes few people question it; “The large body of research on g may give the impression that the g explanation is the only possible explanation… Thus, the g explanation remains very dominant in the current literature” [52]. Other researchers, looking at 600,000 subjects, have found that school itself, rather than some sort of neurological ether, is what makes people’s scores increase in disparate cognitive tasks [53].

By the same logic, what people learn outside of school often does not seem to correlate with “general intelligence” [54]. For example, in Kenya, children who know a lot about their culture’s medicinal herbs (which is considered as a sign of intelligence in their culture) tend to score poorly on Western IQ testing [55][45]. However, many IQ tests have “general knowledge” sections, that is, of the kind of knowledge one learns in school, which is correlated with “general intelligence” [56]. But many psychologists argue that IQ testing, through the g-factor model, is a measure of everything that it means to be human, as 52 psychologists got together to argue that intelligence is not merely “narrow test-taking”, or “book smarts”, but “a broader and deeper capability for comprehending our surroundings… virtually all activities require some reasoning and decision-making.” They also proposed that “intelligence, so defined, can be measured, and intelligence tests measure it well” [57] Recently, in the same vein, the psychology professor Richard Haier argued that an experiment should be done to see if people who score higher on IQ tests need more anesthesia to be sedated, as IQ is a measure of how “conscious” someone is [58].

Psychometrics are not narrative-free. IQ tests were originally used to help struggling students catch up academically in France [59]. Alfred Binet, who developed the first practical IQ test, was distraught to see the use of his test get out of hand; he stated, “A few modern philosophers assert that an individual’s intelligence is a fixed quantity, a quantity which cannot be increased. We must protest and react against this brutal pessimism…” [60]. And there continues to be no evidence that the g-factor model is needed to explain the data presented, making Binet correct.

It is well known that IQ testing has a dark history linked to eugenics; its usage was amplified for political gain. The US government used IQ to justify sterilizing those deemed mentally inferior, often minority groups, and block immigration [25]. It was similarly influential to the start of the Holocaust [25], and Spearman’s seminal work on the g-factor came out about 29 years before it started [22]. Many psychologists want to argue that they have moved past this – IQ testing is now supposedly only used “for good” [61]. But the g-factor, which strips intelligence of any ideas of culture, still has consequences, such as making Western influence always appear “natural” and “healthy”, as one can always argue that the West is helping to “raise” the IQ of other countries.

It also has undiscussed consequences locally. The g-factor model disassociates intelligence with Western education, which makes choosing a less academic or prestigious life path seem inferior, as these decisions are arguably due to “poor neurological wiring”. As a consequence, students are spending more and more time on academic work. Between 1981 and 1997, children spent 18% more time in school, and 145% more time on homework. On the other hand, any time playing, even on a computer, went down 16% [62]. Many students now report that grades are more important to them than friendship [63]. This is a natural consequence of psychologists universalizing and objectifying school; and US education wasn’t created strictly for humanitarian purposes. The government used it to inculcate respect for authority and decrease creativity [64].

As people see themselves through the lenses of testing, the g-factor model makes the only aspects of life that seem to matter are those that are measurable, such as work, school, and money, as one always has to prove their abilities. That is, no one has the right to develop and make mistakes; they should just succeed in a very narrow definition of the term, justified by a perspective of intelligence coming from innate “mental power”.

Little by little, test results are seen as more important than the individuals themselves. And the psychological and psychiatric discourse grows in influence, permeating the legal system.

Those in STEM careers, people exposed to a high amount of testing, are developing technology making it harder to choose an avenue other than higher education, especially in STEM itself. AI is destroying the middle class [34]. At the same time, idiographic humanities, seen as less important, precipitously lose students, letting these problems remain unquestioned. In a world where technology demands more information from its users, human inner experiences are irrelevant to abstract statistics that are also “self-fulfilling”. Similarly, if intelligence is continuously defined narrowly as “whatever IQ tests measure”, then the economy is left in an easy position for AI to outcompete workers, as AI is already successfully being trained to do IQ tests [65].

Lastly, as everybody grows more exposed to the jargon of psychology and psychiatry, it becomes impossible to think of oneself outside of their categories, giving rise to a psychologized subjectivity.

While psychological and psychiatric research often pays lip service to the idiographic and complex approaches, they continue to behave in a universalizing nomothetic fashion that is amplified in society, probably for monetary gains.

Many other branches of knowledge provide extremely relevant insights about the human condition that are often ignored. But nomothetic psychologists and psychiatrists can’t allow the collapse of their categories to happen, as that would imply, that they are, after all, philosophers. Or even, that they are a branch of the law.

One can then conclude that perhaps the mouse runs the lab, and the psychologist is in the maze.

References

[1] Gulbenkian Commission on the Restructuring of the Social Sciences. 1996. Open the Social Sciences: Report of the Gulbenkian Commission on the Restructuring of the Social Sciences. Edited by V. Y. Mudimbe, Bogumil Jewsiewicki, and Immanuel Wallerstein. N.p.: Stanford University Press.

[2] Morin, Edgar. 2006. La naturaleza de la naturaleza. N.p.: Ediciones Cátedra.

[3] Gleick, James. 2008. Chaos: Making a New Science. N.p.: Penguin Publishing Group.

[4] Feuerbach, L. (1957). The Essence of Christianity. Harper & Row.

[5] Egenes, Thomas, and Kumuda Reddy. Eternal Stories from the Upanishads. 1st World Publishing, n.d.

[6] Jahnke, Art. 2015. “The History and Future of Funding for Scientific Research | The Brink.” Boston University. https://www.bu.edu/articles/2015/funding-for-scientific-research/.

[7] “Psychologists : Occupational Outlook Handbook: : U.S.” 2022. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/life-physical-and-social-science/psychologists.htm#tab-3.

[8] “29-1223 Psychiatrists.” 2022. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/oes/current/oes291223.htm.

[9] Foucault, Michel. 1976. Vigilar y castigar: nacimiento de la prisión. N.p.: Siglo Veintiuno Editores.

[10] Han, Byung-Chul. 2020. The Disappearance of Rituals: A Topology of the Present. Translated by Daniel Steuer. N.p.: Wiley.

[11] National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics (NCSES). 2022. Federal Funds for Research and Development: Fiscal Years 2020–21. NSF 22-323. Alexandria, VA: National Science Foundation. Available at https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf22323/.

[12] “FY23 Budget Outcomes: National Science Foundation.” 2023. American Institute of Physics. https://www.aip.org/fyi/2023/fy23-budget-outcomes-national-science-foundation.

[13] “Agency Profile: National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH).” 2023. USASPENDING.gov. https://www.usaspending.gov/agency/national-endowment-for-the-humanities?fy=2023.

[14] Ortega y Gasset, José. 2003. El tema de nuestro tiempo. N.p.: Austral.

[15] Foucault, Michel. 1991. The Foucault Reader. Edited by Paul Rabinow. N.p.: Penguin Books.

[16] Foucault, Michel. 2000. Power. Edited by Paul Rabinow and James D. Faubion. Translated by Robert Hurley. N.p.: New Press.

[17] Kneale, William and Martha Kneale. 1962. The Development of Logic (p. 2). Clarendon Press.

[18] Kastrup, Bernardo. More Than Allegory: On Religious Myth, Truth And Belief (p. 34). John Hunt Publishing.

[19] Doss, Cheryl (2008) “Logic Systems and Cross-Cultural Mission,” Journal of Adventist Mission Studies: Vol. 4: No. 1, 79-92. Available at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/jams/vol4/iss1/7.

[20] Fuller, R. B., and Kiyoshi Kuromiya. 1981. Critical path. N.p.: St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

[21] Bierce, Ambrose. 1993. The Devil’s Dictionary. Edited by Ambrose Bierce. N.p.: Dover Publications.

[22] Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Charles E. Spearman”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 13 Sep. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Charles-E-Spearman. Accessed 16 March 2023.

[23] Sternberg, Robert J.. “human intelligence”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 11 Apr. 2022, https://www.britannica.com/science/human-intelligence-psychology. Accessed 16 March 2023.

[24] Gottfredson, Linda S. “Schools and the g Factor.” The Wilson Quarterly (1976-), vol. 28, no. 3, 2004, pp. 35–45. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/40260870. Accessed 19 Dec. 2023.

[25] “THE G FACTOR.” 1998. Arthur J Jenson. Accessed March 9, 2023. https://emilkirkegaard.dk/en/wp-content/uploads/The-g-factor-the-science-of-mental-ability-Arthur-R.-Jensen.pdf.

[26] Zimmer, Carl. She Has Her Mother’s Laugh. Penguin Publishing Group.

[27] Zimmer, Carl. 2018. “Can a Genetic Test Find Your Intelligence in Your DNA?” The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2018/05/genetic-intelligence-tests-are-next-to-worthless/561392/.

[28] “Why some people have more consciousness than others?” 2022. YouTube. Accessed March 9, 2023. https://youtu.be/e_DTS0LYmRk?t=387.

[29] Plomin, R. Genetics and general cognitive ability. Nature 402 (Suppl 6761), C25–C29 (1999). https://doi.org/10.1038/35011520

[30] Warne RT, Burningham C. Spearman’s g found in 31 non-Western nations: Strong evidence that g is a universal phenomenon. Psychol Bull. 2019 Mar;145(3):237-272. doi: 10.1037/bul0000184. Epub 2019 Jan 14. PMID: 30640496.

[31] Hambrick, David Z. 2014. “Brain Training Doesn’t Make You Smarter.” Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/brain-training-doesn-t-make-you-smarter/.

[32] Adkins, D. C. (1937). The effects of practice on intelligence test scores. Journal of Educational Psychology, 28(3), 222–231. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0055460 ‘

[33] Trend, David, Jeff Melnick, Jennifer Ruth, Reshmi Dutt, Bertin M. Louis, Deepa Kumar, Alexandra Martinez, et al. 2022. “75% of New Jobs Require a Degree While Only 40% of Potential Applicants Have One.” Truthout. https://truthout.org/articles/75-of-new-jobs-require-a-degree-while-only-40-of-potential-applicants-have-one/.

[34] Markovits, Daniel. The Meritocracy Trap. Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

[35] “Top psychologist: IQ is the No. 1 predictor of work success—especially combined with these 5 traits.” 2022. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/07/11/does-iq-determine-success-a-psychologist-weighs-in.html.

[36] Friedman, Lex. 2022. “How to become smarter: Is it possible? | Richard Haier and Lex Fridman.” YouTube. Accessed March 9, 2023. https://youtu.be/UUwjXITMfBU?t=281.

[37] Kees-Jan Kan, Han L.J. van der Maas, Stephen Z. Levine, Extending psychometric network analysis: Empirical evidence against g in favor of mutualism?, Intelligence, Volume 73, 2019, Pages 52-62, ISSN 0160-2896, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2018.12.004.

[38] Douglas K. Detterman, Does “g” exist?, Intelligence, Volume 6, Issue 2, 1982, Pages 99-108, ISSN 0160-2896, https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-2896(82)90008-3.

[39] L.J., Han, Kees Kan, and Denny Borsboom. 2014. “J. Intell. | Free Full-Text | Intelligence Is What the Intelligence Test Measures. Seriously.” MDPI. Accessed March 10, 2023. https://www.mdpi.com/2079-3200/2/1/12.

[40] Factor Analysis at 100. Taylor and Francis.

[41] “Work of forgotten IQ pioneer Godfrey Thomson on show.” 2016. BBC. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-scotland-edinburgh-east-fife-36894717.

[42] “Testing & Educational Support in the US – Market Size 2004 – 2029.” 2023. IBISWorld. https://www.ibisworld.com/industry-statistics/market-size/testing-educational-support-united-states/.

[43] Kovacs, K., & Conway, A. R. A. (2019). What is IQ? Life beyond “general intelligence”. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(2), 189–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721419827275

[44] Ritchie SJ, Tucker-Drob EM. How Much Does Education Improve Intelligence? A Meta-Analysis. Psychol Sci. 2018 Aug;29(8):1358-1369. doi: 10.1177/0956797618774253. Epub 2018 Jun 18. PMID: 29911926; PMCID: PMC6088505.

[45] American Psychological Association. (2003, February 1). Intelligence across cultures. Monitor on Psychology, 34(2). https://www.apa.org/monitor/feb03/intelligence.

[46] Jacques Grégoire, Lawrence G. Weiss, Chapter 8 – The Flynn Effect and Its Clinical Implications, Editor(s): Lawrence G. Weiss, Donald H. Saklofske, James A. Holdnack, Aurelio Prifitera, In Practical Resources for the Mental Health Professional, WISC-V (Second Edition), Academic Press, 2019, Pages 245-270, ISBN 9780128157442, https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-815744-2.00008-2.

[47] “IQ Testing.” n.d. DC Fagan Psychological Services. Accessed March 10, 2023. https://www.dcfagan.com/services/iq-testing/.

[48] Shenk, David. 2011. The Genius in All of Us. N.p.: Penguin Random House.

[49] Joseph, Jay. 2015. The Trouble with Twin Studies. N.p.: Routledge.

[50] Kaufman, Scott. Ungifted. Basic Books.

[51] Keivit, Rogier. 2018. “IQ and Society.” Scott Barry Kaufman. https://scottbarrykaufman.com/iq-and-society/.

[52] Van Der Maas, H. L. J., Dolan, C. V., Grasman, R. P. P. P., Wicherts, J. M., Huizenga, H. M., & Raijmakers, M. E. J. (2006). A dynamical model of general intelligence: The positive manifold of intelligence by mutualism. Psychological Review, 113(4), 842–861. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.113.4.842

[53] Kievit R, Simpson-Kent I and Fuhrmann D (2020) Why Your Mind Is Like a Shark: Testing the Idea of Mutualism. Front. Young Minds. 8:60. doi: 10.3389/frym.2020.00060.

[54] “The Effectiveness of Triarchic Teaching and Assessment | The National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented (1990-2013).” n.d. National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented. Accessed March 10, 2023. https://nrcgt.uconn.edu/newsletters/spring002/.

[55] Robert J Sternberg, Catherine Nokes, P.Wenzel Geissler, Ruth Prince, Frederick Okatcha, Donald A Bundy, Elena L Grigorenko, The relationship between academic and practical intelligence: a case study in Kenya, Intelligence, Volume 29, Issue 5, 2001, Pages 401-418, ISSN 0160-2896, https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-2896(01)00065-4. (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0160289601000654)

[56] Adrian Furnham, Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, Personality, intelligence and general knowledge, Learning and Individual Differences, Volume 16, Issue 1, 2006, Pages 79-90, ISSN 1041-6080, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2005.07.002.

[57] “Mainstream Science on Intelligence.” 1994. University of Delaware. Accessed March 10, 2023. https://www1.udel.edu/educ/gottfredson/reprints/1994WSJmainstream.pdf.

[58] Fridman, Lex. 2022. “Richard Haier: IQ Tests, Human Intelligence, and Group Differences | Lex Fridman Podcast #302.” YouTube. Accessed March 10, 2023. https://youtu.be/hppbxV9C63g?t=8361.

[59] Ted-ed. 2021. “The dark history of IQ tests – Stefan C. Dombrowski.” https://youtu.be/W2bKaw2AJxs.

[60] n.d. Lane Community College. https://classes.lanecc.edu/pluginfile.php/2668411/mod_resource/content/0/Mindset%20Excerpt%20pg%202.pdf.

[61] “IQ Tests Have a Dark History — but They’re Finally Being Used for Good.” 2017. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/iq-tests-dark-history-finally-being-used-for-good-2017-10.

[62] Lukianoff, Greg; Haidt, Jonathan. The Coddling of the American Mind. Penguin Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

[63] Iqbal, Nosheen. 2018. “Generation Z: ‘We have more to do than drink and take drugs.’” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2018/jul/21/generation-z-has-different-attitudes-says-a-new-report.

[64] Gatto, John T. 2009. Weapons of Mass Instruction: A Schoolteacher’s Journey Through the Dark World of Compulsory Schooling. N.p.: New Society Publishers.

[65] Hersche, M., Zeqiri, M., Benini, L. et al. A neuro-vector-symbolic architecture for solving Raven’s progressive matrices. Nat Mach Intell (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-023-00630-8