Part 1: Atomic Bombs

So long as national States exist and fight each other, only inefficiency can preserve the human race. To improve the fighting quality of separate States without having any means of preventing war is the road to universal destruction.

––Bertrand Russell, The History of Western Philosophy

When a country creates the first nuclear bomb, the rest of the nations, confronted by these pressing circumstances, have to ask themselves whether they should make their own in response. Those who decide not to develop a nuclear weapon run the risk of being subdued militarily, politically, and economically by the other nations who chose to create one.

Although the usage of these weapons could put an end to human existence, this hasn’t stopped those who engage in the creation of these atomic weapons from continuing to devote large amounts of resources towards programs that aim to expand these military technologies.

However, such “arms races” extend way beyond the confines of thermonuclear technologies, and occur in different, sometimes unexpected, contexts.

The Agricultural Revolution brought an end to many hunter-gatherer societies. Agriculturalists could use the excess food that was produced in the fields to sustain specialized bureaucratic and military classes, which didn’t have to devote their time and energy to the arduous task of growing their own food. Faced with these severe conditions, nomadic groups couldn’t keep up with their counterparts who settled in cities.

Similarly, the Industrial Revolution at the turn of the 19th century posed a threat to agricultural societies. Those who weren’t quick to industrialize soon could find themselves outpaced by the exacerbated rhythms of production brought by machinery. This was demonstrated in the United States during the Civil War with devastating results, when the industrialized North defeated an agriculturally driven South.

Part 2: An unexpected nuclear bomb

One of the biggest “atomic bombs” of all time took place during the 19th century, and even though its effects extend all the way to the 21st century with an enormous force, its history remains suspiciously opaque. This bomb was rooted in the publication of On the Origin of the Species, by Charles Darwin, in 1859.

Within his text, Darwin analyzed a practice that was common during his time period among the wealthy: pigeon breeding. Darwin had seen for himself that when breeders decide to only select pigeons of certain characteristics to mate, such as those of a smaller beak or of a certain hue, it only takes three to six years of breeding for substantial effects to occur, where the offspring significantly display that characteristic. Darwin argued that, even though breeders may start from just one species of common pigeon, the “diversity of the breeds is something astonishing”, when the breeders use this “artificial selection” to create the variety that they want [a]. Charles Darwin, also noting how artificial selection is a standard technique in agriculture, argued that nature does the same thing to create entirely new species. Nature encourages some animals and plants to breed, and kills off others, which eventually exaggerates certain traits, leading to the diversity of the species [1].

![Drawings of different breeds of rock pigeon from a book published in 1887 [b] Drawings of different breeds of rock pigeon from a book published in 1887 [b]](https://unexaminedglitch.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/rsw1280-71662306-9341-4059-bcdf-9f1bfc056935.jpg)

Charles Darwin’s cousin, Francis Galton, read On the Origin of the Species and used it to make a new “atomic bomb”. Galton was a rich Cambridge graduate who inherited his money from the slave, gun, and banking trades. Already a famous British geographer and meteorologist himself, he was friends with some of the most prestigious thinkers of his time. Galton saw Darwin’s work from the perspective of an engineer, his goal: the improvement of England.

If the State needed to be strong, what was stopping it from controlling the sexual reproduction of its individuals, in order to make them embody the ideals of the nation? Francis Galton argued that the government should create the conditions for artificial selection to biologically modify the members of the country, similar to how pigeons can be carefully bred [c]. Individuals with favorable traits should be encouraged to have children, perhaps through subsidies, while those with unfavorable traits should be discouraged from reproducing (although Galton was often ambiguous as to exactly how) [2].

It had been recently discovered that the levels of brightness of stars followed a statistical bell curve, a state of the art mathematical construct. The astronomer Adolphe Quetelet, compiling data on human height, was surprised to realize that this so-called “Gaussian distribution” also applied to human traits. Adolphe Quetelet took measurements of human height and saw that it similarly follows a bell curve, with a few individuals being extremely tall, a few extremely short, and most in the middle, as seen in the graph:

![The state of the art at the time was that height followed a Gaussian distribution, also called a normal distribution. Francis Galton noted that most people’s height was rather average, except for rare cases that deviated from the norm, where someone’s height was either way shorter or way taller. Therefore, people’s height follows a bell curve, as shown by Galton in the image [3]. The state of the art at the time was that height followed a Gaussian distribution, also called a normal distribution. Francis Galton noted that most people’s height was rather average, except for rare cases that deviated from the norm, where someone’s height was either way shorter or way taller. Therefore, people’s height follows a bell curve, as shown by Galton in the image [3].](https://unexaminedglitch.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/rsw1280-9f0ae9a9-6db2-4803-ad44-1e13d7196aae.jpg)

Quetelete’s ideas provided a framework to Galton [3], who, after studying his work, envisioned that it could be used as a tool to advance Darwinism [4], even to the point of creating a new field [2][5].

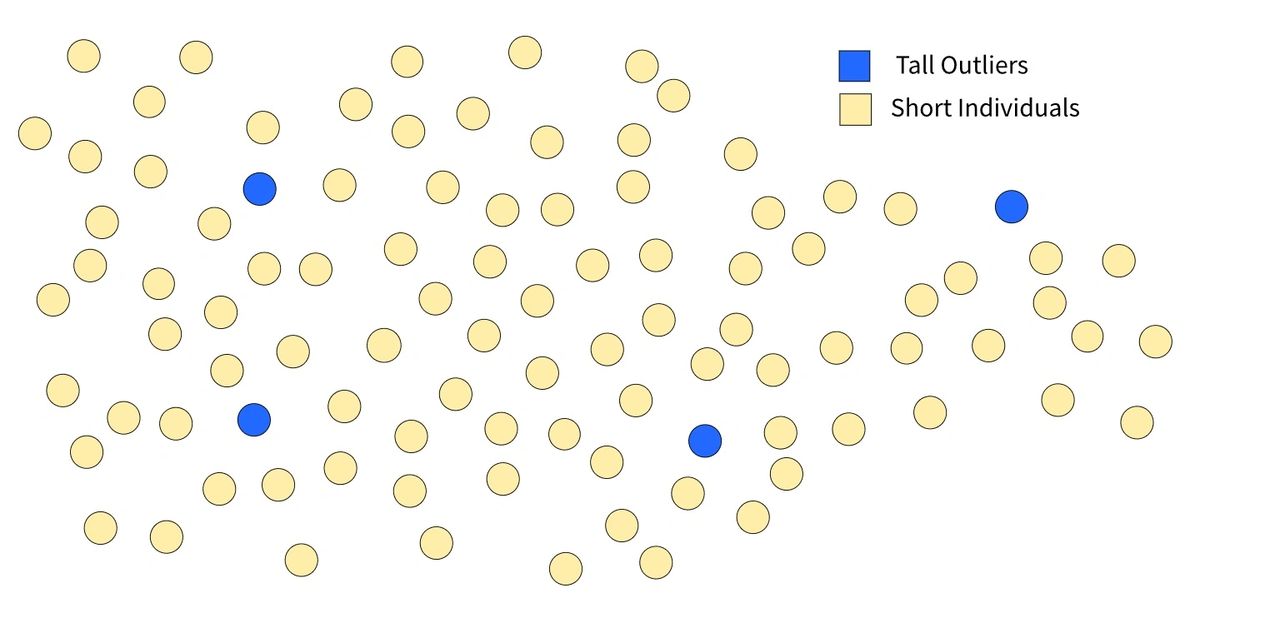

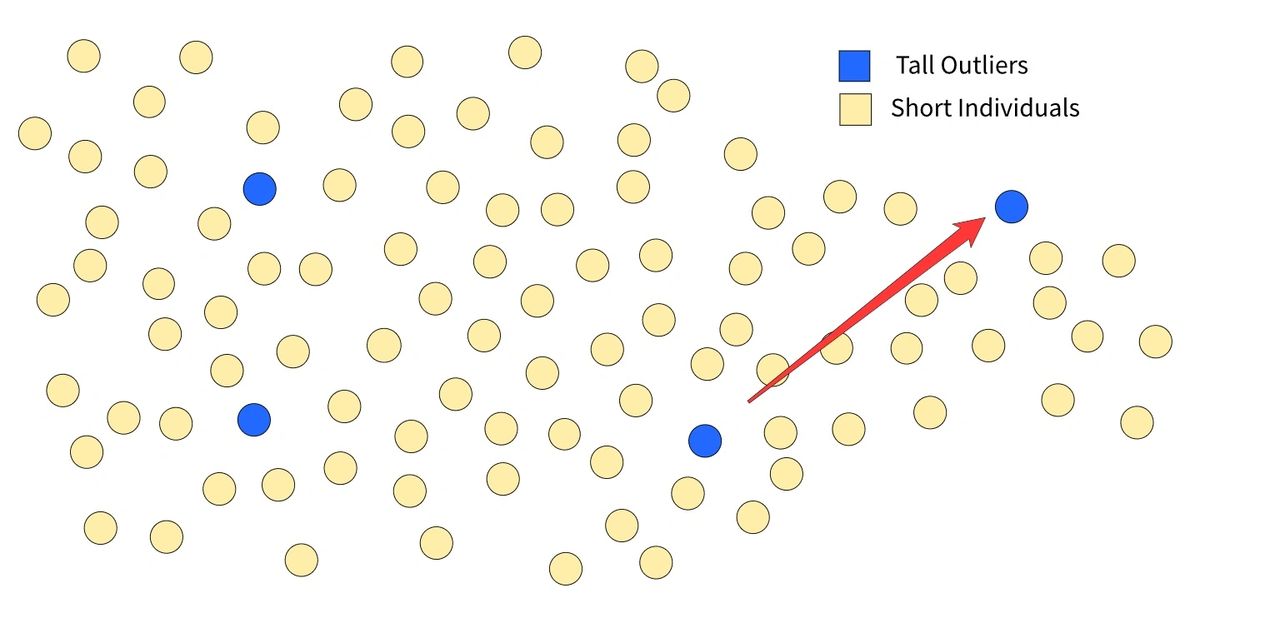

Galton imagined that in a world without any reproductive restrictions, where individuals were allowed to freely choose their partners, tall outliers would end up with partners who were shorter than themselves. After all, there were few outliers to begin with, therefore, chances were, tall outliers would find a shorter partner. Once tall outliers mixed with those whose height was in a shorter bracket, their children would likely be shorter than the tall outliers themselves; this constituted a “regression towards the mean”. Even if two tall outliers happened to pair up, and produced a tall child, chances are that their children or grandchildren would pair with someone shorter. Therefore, whenever there is a tall outlier, eventually, the offspring “regress” right back down to average height.

In other words, outliers regress to the mean since they have a high chance of mixing with average or shorter people. If one wanted to increase the height of a population, it would be necessary to carefully control the conditions for reproduction: the tall outliers would have to artificially stay away from the shorter members of the population [3].

![In Galton’s system, tall outliers are spotted and set apart by a barrier of social restrictions. The tall outliers are encouraged to breed, while everyone else is discouraged from doing so. Even taller outliers subsequently appear; they are set aside as well. The process goes on. Eventually, the original blue group is short in comparison with the newer generations [6]. In Galton’s system, tall outliers are spotted and set apart by a barrier of social restrictions. The tall outliers are encouraged to breed, while everyone else is discouraged from doing so. Even taller outliers subsequently appear; they are set aside as well. The process goes on. Eventually, the original blue group is short in comparison with the newer generations [6].](https://unexaminedglitch.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/rsw1280-bc183f6d-a06b-4201-b277-a9a597d697c6.jpg)

Further research conducted by Galton himself led him to discover that the child of two tall outlier parents is usually somewhat shorter than that same child’s parents. Galton argued that this was because the tall outlier parents didn’t have “purely” tall inheritable traits, but were also carrying inheritable traits from their short distant ancestors [4]; this was another possible way for the tall outliers to “regress towards the mean”, or tend back towards the average height [6]. He argued that tall families would have to be kept as “pure” as possible for the tallest population to be reached. The best system, if a theoretical society wanted height, was for the tall outliers to only be able to mate with other tall outliers [2].

However, height wasn’t the point of Galton’s research, as making people grow increasingly taller as generations went by wasn’t an objective worth pursuing. A different goal was more appealing, especially to a scientist like Galton, who took pride in his wits: What if one could make human intelligence grow, just like the necks of artificially selected pigeons?

Thus, the British nation [d] could become stronger by creating mechanisms of reproductive control that would enable intelligence to be artificially enhanced. This was the objective of his book Hereditary Genius, published in 1869. In this book, he attempted to show that “eminence”, that is to say, exceptional intelligence and talent, runs through certain families as an inheritable trait. Taking grades from a math class in Cambridge, he discovered that the scores of the students seemed to follow a bell curve, just like Quetelet’s height distribution did.

Then Galton inferred:

“If this be the case with stature, then it will be true as regards every other physical feature— as circumference of head, size of brain, weight of grey matter, number of brain fibres, etc.; and thence, by a step on which no physiologist will hesitate, as regards mental capacity.”

Galton pointed out that what he wanted to do had already happened historically, just not how he intended it to be done:

“The long period of the dark ages under which Europe has lain is due, I believe in a very considerable degree, to the celibacy enjoined by religious orders on their votaries. Whenever a man or woman was possessed of a gentle nature that fitted him or her to deeds of charity, to meditation, to literature, or to art, the social condition of the time was such that they had no refuge elsewhere than in the bosom of the Church. But the Church chose to preach and exact celibacy. The consequence was that these gentle natures had no continuance, and thus, by a policy so singularly unwise and suicidal that I am hardly able to speak of it without impatience, the Church brutalized the breed of our forefathers. She acted precisely as if she had aimed at selecting the rudest portion of the community to be, alone, the parents of future generations. She practised the arts which breeders would use, who aimed at creating ferocious, currish and stupid natures. No wonder that [nonsensical laws] prevailed for centuries over Europe; the wonder rather is that enough good remained in the veins of Europeans to enable their race to rise to its present, very moderate level of natural morality” [3].

In Galton’s view, biology plays a fundamental role in the collapse of civilizations. If a government doesn’t exert control over its citizen’s reproductive life, the degradation of the “stock” of its nation inevitably follows, as intelligent, eminent outliers are easily lost. This dooms society to failure, because their desirable traits are lost with them, and the undesirable ones spread out of control. Therefore, strong morals have to be created around marriage and reproduction, including deterring people from mixing outside of their biological classes [e], and keeping those who are deemed undesirable in a celibate state [f]. Additionally, in Galton’s view, migration should be strictly regulated. Uncontrolled immigration leads to foreigners with undesirable traits entering the nation and bringing down the quality of its stock. On the other hand, uncontrolled emigration leads the eminent, exceptional individuals of the nation to leave in search of different lands [3], which today is called “brain drain” .

The implications of this new way of thinking would have made any politician’s flesh creep in any country. Francis Galton labeled his new atomic bomb “eugenics”, which he defined as “the study of agencies under social control that may improve or impair the racial qualities of future generations either physically or mentally” [7] He derived the term from the Greek word “eugenes”, meaning “good in birth” or “good in stock” [8].

If Galton was right, just a few generations down the line, those countries that took political action in favor of eugenics, through a process of careful artificial selection, would have created a population that was more intellectually and physically capable than any country that didn’t. On top of this, they could use their economic resources in a more efficient way by decreasing the cost of social services for those who were deemed “unfit”. That is to say, any country that didn’t engage in these practices was likely doomed to be outplayed down the line, as it wouldn’t be able to compete anymore in the international arena.

To those who decided to embrace eugenics, time was of the essence, as not engaging in these policies quickly enough would have created an ever bigger, perhaps even insurmountable, gap between those countries at the lead, and those that were lagging behind.

While measuring the height of the population was simple, measuring intelligence and mental faculties was a more intricate task. Francis Galton dedicated the rest of his life to try to devise ways to measure those elusive traits, as he wanted the State to one day use these tools to steer heredity in the direction that it wanted [2].

Galton pioneered the psychological questionnaire and the study of personality [2], created the term “gifted” in educational psychology [3][9], invented the twin study [10], helped found biometrics [2], coined the “nature vs. nurture” debate in psychology [5], and created one of the first psychological laboratories in the world, which he called his “anthropometric laboratory” [2]. Galton even founded much of the basis of modern statistics – including correlation, decile, quartile, percentile, median, the regression line, and, as has been mentioned above, regression towards the mean [11]. Hereditary Genius was the first work to statistically examine the inheritance of a human faculty and arrive at numerical results [2], and, indeed, Galton is considered the founder of psychometrics [5] and behavioral genetics [12], and one of the founders of psychology itself. He wrote over twenty books and hundreds of papers, some of which are still cited in modern scientific articles. Francis Galton, considered a polymath [2], was even knighted in 1909 [13]. His student and disciple, the eugenicist Dr. Karl Pearson [2], would go on to found the field of mathematical statistics [14], and even inspire the works of Albert Einstein [15].

Part 3: The legal conflict

Aristotle [16] defined justice as the “ordering principle of society”. He imagined that there were two main forms of justice, or templates to order society: democracy and oligarchy. The democrats, Aristotle claimed, believe that justice is based on equality, while the oligarchs believe that justice is based on inequality. Therefore, to Aristotle, a democratic order demands an equalizing principle, while an oligarchical system requires a principle to substantiate treating people unequally.

Galton had developed a new way to sustain oligarchical rule in a secularized world: Darwinism, where intelligence would be proposed as the basis for inequality. He had devised an early IQ system, flirting with the idea of being able to objectively measure the worth of individuals, and, subsequently, assign them the societal power that they deserve in accordance to their level of intelligence [3].

Politically, Galton advocated for a combination of determinism, (a direct rejection of free will) [17], united with intelligence assessments, where technocrats took over the control and regulation of society through the usage of statistical data [2]. This had profound implications.

In the decades before Galton published his ideas, wars were taking place in different continents, in an attempt to set up a new conception of justice based on democratic ideals. These ideas that were brought forward by the Enlightenment, had, at their core, free will as the foundation of justice, in an attempt to equalize people in front of the law. It was a system directly antithetical to Galtonian politics.

The Enlightenment and the French Revolution conceived of justice based on the ideals of “egalité, fraternité, liberté” (“equality, fraternity, freedom”), as an adversary to the absolutism of European monarchies. This system would find one of its most relevant expressions in the penal field.

Attempting to replace the penal system of the monarchical ancien régime, plagued by torture, abuses, and absence of coherent standardized procedures, Italian philosopher, Cesare Beccaria [18], formulated a new way for the State to deal with crimes and punishments, based on a process that would attempt to set all the citizens as equals in front of the law.

In Beccaria’s penal system, laws would be passed that prohibited certain behaviors. The laws needed to be stated clearly in order for them to limit the interpretations of judges, which would prevent them from abusing their power. Penal codes would follow a simple syllogistic formula, according to Aristotelian logic; this looked like: “He who murders goes to prison for 30 years. John murdered. Therefore, John goes to prison for 30 years”.

Who John is doesn’t matter under Beccaria’s conception of the law. The judge is not there to understand John’s personality, his biography, or family background; he isn’t there to understand John’s thoughts either. The job of the judge is simply to determine whether a forbidden behavior has taken place, who did it, and punish it in accordance with the precepts of the law.

The cornerstone that grants equality in front of the law within this system is free will. Everyone, regardless of who they are, would be presumed to act freely, and therefore they would be responsible for their acts; this is what is known as “moral responsibility”.

There are two main reasons to base the entirety of the penal system on the idea of free will, according to Beccaria [g]:

- If the State considered the individual conditions of the people who are tried, that is to say, their psychological traits, and the causes that led them to behave, and so on, one would need an infinite penal code, as there are endless causes that can lead a person to commit a crime.

- There is no way to know for sure what leads people to act in one way or another, as no one can truly “get inside someone else’s head”. It is difficult enough to prove whether or not a forbidden behavior has been committed, let alone the perpetrator’s inner states.

This system of free will also provides to all the citizens a certain anonymity and privacy in front of the State that grants everyone the right to be judged equally. Why? Because the State wouldn’t judge who people were, instead, its role was to judge whether a forbidden behavior had taken place or not. Similarly, every citizen should be granted certain rights for the mere fact of being a human, regardless of who they were.

The idea of free will was Beccaria’s democratic answer to the demands of an “equalizing, democratic principle”. What people do isn’t necessarily who they are in the eyes of the State. Therefore, committing a crime doesn’t necessarily say much about the criminal themselves, they have the free will to choose to commit a crime again, or not to do so.

His system had the goal of preventing crimes, however, he was not attempting to do so through a scientific formula. “Do you want to prevent crimes?” asked Beccaria . “Then make sure that the laws are clear and simple and that the whole strength of the nation is concentrated on defining them, and that no part of it is used to destroy them. Make sure that the laws favor individual men more than classes of men. (…) uncertainty in its laws will maintain and increase the country’s idleness and stupidity” [18].

Models that saw individuals as “rational agents”, who were able to play an active role and participate in the political arrangement of the community, were conceived during a time when humanistic doctrines sprouted and configured a new way of understanding the political landscape.

Cesare Beccaria’s importance can hardly be overstated [h], given that his work was influential in the creation of the Constitution of the United States, as well as the 1789 French Declaration of Rights of Man and of the Citizen. These documents ignited democratic movements and placed the individual as the basis of legal systems worldwide, profoundly shaping contemporary legal thought.

Part 4: Beccaria’s opposition

While today’s wide adoption of Beccaria’s system can make it seem like a natural, obvious way to organize the legal structure, when his Essay on Crimes and Punishments was published in 1764, he received fierce opposition by those who were in favor of torture as an integral part of the judicial system. Even Enrico Ferri, who, many years after Beccaria’s death became one of his highly critical intellectual adversaries, acknowledged the rough historical context in which Beccaria published his seminal book and his importance in changing the political landscape, when he said [19]:

“When Cesare Beccaria printed his book on crime and penalties […] under a false date and place of publication, reflecting the aspirations which gave rise to the impending hurricane of the French revolution; when he hurled himself against all that was barbarian in the medieval laws and set loose a storm of enthusiasm among the encyclopedists, and even some of the members of government, in France, he was met by a wave of opposition, calumny and accusation on the part of the majority of jurists, judges and lights of philosophy. The abbé Jachinci published four volumes against Beccaria, calling him the destroyer of justice and morality, simply because he had combatted the tortures and the death penalty.”

Given that in the 21st century defenses of torture are no longer in vogue, one is left wondering what mindset could see its removal as the destruction of justice and morality. Ferri goes on:

“The tortures, which we incorrectly ascribe to the mental brutality of the judges of those times, were but a logical consequence of the contemporaneous theories. It was felt that in order to condemn a man, one must have the certainty of his guilt, and it was said that the best means of obtaining […] certainty, the queen of proofs, was the confession of the criminal. And if the criminal denied his guilt, it was necessary to have recourse to torture, in order to force him to a confession which he withheld from fear of the penalty. The torture soothed, so to say, the conscience of the judge, who was free to condemn as soon as he had obtained a confession. Cesare Beccaria rose with others against the torture. Thereupon the judges and jurists protested that penal justice would be impossible, because it could not get any information, since a man suspected of a crime would not confess his guilt voluntarily. Hence they accused Beccaria of being the protector of robbers and murderers, because he wanted to abolish the only means of compelling them to a confession, the torture.”

Part 5: Galton’s skepticism of free will

Francis Galton, as many others after him, saw free will as a matter to be resolved through scientific lenses. Galton believed that anything that seemed like a free will choice, was, only in a matter of time, going to be uncovered to be biologically caused, discovered through his burgeoning science of psychometrics. He believed that the idea of an independent “Self” was illusory; the human person is “little more than a conscious machine, the larger part of whose actions are predictable” [17].

To Galton, if free will doesn’t exist, the idea that lawyers and philosophers could create a well organized, harmonic society was ultimately hopeless. Scientists should be the ones to come up with solutions, as humans are not “rational agents”, but puppets guided by cruel evolutionary forces that need to be tamed. It was just a matter of time until scientists finally figured out the puzzle of the natural laws governing human behavior, consequently unleashing a technocratic utopia.

However, scientists continue to misapprehend, and in many cases, even make a mockery, of the role of free will and the reasons why it was given its foundational role in the judicial structure.

In Beccaria’s system, saying that someone has free will doesn’t make sense outside the context of democracy. Since the rules that individuals pass embody their best interest, they are fair, and going against the rules means to go against themselves. Within this system, it could be said that a criminal is often the result of unfair laws. Claiming that an individual has free will is a heuristic that attempts to resolve the tension between the interests of the individual, and the interests of the community.

Beccaria wasn’t making a scientific claim when he assembled his system around free will, he understood that there were causes for behavior. Free will was meant to be an equalizer that provided certain privacy and anonymity in front of the law, as the State didn’t judge people for who they were, but for their actions.

Additionally, free will provided a simple syllogistic formula that attempted to make the laws clear and transparent, as a way to limit the interpretation of judges, preventing them from abusing their power. Syllogisms, with their simple parameters, constrained judges from making decisions outside of instituted laws that were agreed upon by the community. If the laws were obscure and unclear, judges could do as they pleased, making the system unfair. If the laws were too long for anyone to grasp, their extension wouldn’t allow the public to know them, making them illegitimate.

On the other side, Galton’s system describes humans as organically imperfect beings, crawling their way to secularized Darwinian heaven. In Galtonian thought, there is always a higher evolutionary plane to aspire for. The role of the individual is set aside, as evolutionary progress becomes the new protagonist, taking the center of political action, while scientific elites pull the strings of government.

Francis Galton believed that this ultimately justified punishing “undesirables” of “lower intellect” or other disadvantage who refused to remain celibate, in order to improve the biological traits of the population. In addition, the most “eminent” people should receive political benefits to encourage them to breed.

In Hereditary Genius Galton argued, “The best form of civilization in respect to the improvement of the race, would be one in which society was not costly; where incomes were chiefly derived from professional sources, and not much through inheritance; where every lad had a chance of showing his abilities, and, if highly gifted, was enabled to achieve a first-class education and entrance into professional life, by the liberal help of the exhibitions and scholarships which he had gained in his early youth; where marriage was held in as high honour […] where the weak could find a welcome and a refuge in celibate monasteries or sisterhoods, and lastly, where the better sort of emigrants and refugees from other lands were invited and welcomed, and their descendants naturalized” [3].

The 19th century, when Galton was developing his ideas, was a time characterized by drastic economic changes in England, as technology boomed from the Industrial Revolution, those who were dispossessed by an agricultural feudalist system were moving to industrialized cities, in hopes of improving their material conditions. However, for many people, the quality of life of the cities was also extremely low. Poverty in industrial cities was high; the poor working classes were deprived of labor rights, barely remunerated in their jobs. They lived in unhygienic, overcrowded housing, in circumstances that fostered sicknesses. Others were vagrants. This dismal situation was described by Friedrich Engels in his work The Condition of the Working Class in England [20].

These conditions were interpreted by eugenicists who belonged to the highest classes as a demonstration of reproductive chaos, which needed swift policies to be resolved. “Undesirables” were quickly spreading.

Part 6: The Italian School of Positive Penal Law: The scientific turn of the law

Beccaria’s system [18], which was at the forefront of legal thought during the 18th century, rested, as it has been mentioned earlier, upon several pillars, such as the rejection of corporal punishments and torture, as well as the promotion of democracy, free will, humanism, and the creation of standardized penal codes based on syllogistic formulas. Beccaria had outlined that, while for practical reasons it was necessary to assign some blame on the individual, criminality is also a failure on the side of legislation. That is to say, the State has the duty of creating fair laws that keep the best interest of the citizens at heart, while favoring privileged groups, to the detriment of everyone, is seen as unethical and counterproductive. Implementing these ideas correctly should avoid a situation where unfair laws push citizens to act against their own well being, and, therefore, it stops individuals from being forced into crime by the very rules that are supposed to protect them.

After all, if just rules were passed that had the best interests of the individuals in mind, why would someone violate these rules and effectively act against themselves? Furthermore, if the laws were unfair, how could anyone request the citizens to follow them?

Punishment is only legitimized because laws keep the best interest of the population at heart. Crime is not conceived as a medical, biological or psychological condition. It is a problem to be solved by legal scholars.

And Beccaria did accomplish his vision of decreasing torture. After reading Beccaria’s Essays on Crimes and Punishments, Catalina II of Russia, Maria Teresa of Austria, Peter Leopold of Tuscany, Joseph II, and Louis XVI, all abolished torture in their kingdoms in the late 1700s [21].

However, by the 1860s, industrialization had granted credibility and importance to scientific discourse, as major technological developments were changing the economic landscape. The natural world was already being closely examined, the time was coming for humans to be scrutinized as well. Darwin had finished On the Origin of the Species [1], inaugurating that “In the distant future I see open fields for far more important researches. Psychology will be based on a new foundation, that of the necessary acquirement of each mental power and capacity by gradation. Light will be thrown on the origin of man and his history.”

It was not only possible to think of humans from a legal perspective, as subjects in possession of inalienable rights, citizens. There were also the diametrically opposed lenses of science that could conceive a human as yet another object to be analyzed, studied, and experimented with. Beccaria wanted to ignore the psychological reasons for why someone committed a crime, as he thought it would be impossible and impractical to do so. But within this new perspective, the genesis of criminality is just another scientific question found in natural forces. One could engineer the way out of it.

In England, Galton’s main ideas about how to deal with crime circled around stopping criminals from reproducing, in accordance with his eugenic thought. Within Galtonian thought, criminality and lack of intelligence were often conflated [22]. But not everyone was fully convinced. In one instance, in the year 1904, one of the attendees to a conference led by Galton said [23]:

“I am not even satisfied by the suggestion Dr. Galton seems to make that criminals should not breed. I am inclined to believe that a large proportion of our present-day criminals are the brightest and boldest members of families living under impossible conditions, and that in many desirable qualities the average criminal is above the average of the law-abiding poor and probably of the average respectable person. Many eminent criminals appear to me to be persons superior in many respects —in intelligence, initiative, originality— to the average judge. I will confess I have never known either.”

The name of this attendee was H. G. Wells.

Darwinism had also severely wounded a conception of humanity as an end in itself. In light of evolution, it was harder than ever to claim that humans were somehow the highest possible entity and the protagonist of a cosmic drama. If, for a long time, it was said that humans had descended from the heavens, these new ideas came in to say that the opposite was true, humans were the result of a vast, crawling struggle of lower beings that, through long periods of time, diverged and increased in complexity. Humans were not to be seen as protagonists, but merely as one of the many entities that competed, without a clear end or aim. As if that wasn’t enough, evolution was not necessarily going to continue to move in “ascension”, there were many instances in which animals could “retrogress” transgenerationally into a state of less sophistication.

If mutations were not pointing in any specific direction, some of those lines could conceivably end up with lower forms. This is what Galton wanted to stop, but he wasn’t the only scientist who was interested in human evolution, and the many paths that it could take.

In On the Origin of Species [1], Darwin foresaw the obvious criticism that, if living beings were changing cross-generationally, these changes had to leave behind traces. Where was the clear physical evidence, the bodies that could, without any doubts, show the gradual changes from one species into another? Darwin reasonably argued that the available records were imperfect, but that didn’t mean his theory was incorrect. Animals migrated, making it hard to collect such traces, and, on top of that, it is unlikely for their bodies or fossils to have the right environmental conditions for them to be preserved properly for study. However, there was enough evidence to show some distant connections among different species. That was enough for Darwin at the time.

The door was left open, inviting contemplation of a fundamental issue: the absence of remnants of humanity’s less developed ancestors and the elusive missing link that bridges mankind to its evolutionary past.

In Italy, in 1871, a man inspecting dead bodies came up with an angle. He concluded that the missing link was way closer than anyone had imagined.

While studying the differences between the “savages” and the “civilized” peoples, hoping to find anthropological ways in which different races contrasted with each other, physician Cesare Lombroso [21] was struck by an idea when he observed the oddly-shaped skull of a thief: Maybe there was a different species or race of humans that so far had been overlooked, namely, the criminal.

Lombroso had access to the skull of a famous Italian thief whose name was Villella. Studying it, he discovered a series of traits that he thought resembled what he expected, not of a human skull, but of the skull of a lower species, or an inferior vertebrate. Lombroso recounted his experience as, “In view of these strange anomalies […] the problem of the nature and origin of crime seemed to me as solved: the characters of primitive men and inferior animals were reproducing in our times.”

Lombroso became even more convinced when he found similar skull anomalies in another criminal, Verzini, who had killed several women, cutting them into pieces and drinking their blood.

As a result, Lombroso thought that he had found the missing link of Darwinism [21], an intermediate stage between the primitive animals and modern humans. The missing link was “the born criminal”, a leftover from an earlier time. One of Lombroso’s biographers described this in 1912 as:

“There are born criminals, representing the type of mankind which existed before the origin of law, the family, and property, and that the representatives of long past conditions thus thrust upon our own time are incapable of respecting the security of life and property and other legal rights” [24].

Lombroso, loyal to positivism, was convinced that the cosmos was ruled by universal physical laws that guided not only the objects that could be found in nature, but also humans. In which case, free will made little sense. In the words of his biographer, Lombroso thought that: “Certain human actions by which the safety of society is endangered are no less determined than is the secretion of the urine or the heart’s beat” [24].

Meanwhile, in England, Galton also wrote extensively about how convinced he was of the inexistence of free will. But this wasn’t his only interest, at some point he even took the time to write to a newspaper some thoughts on how punishments should be administered, a piece that reflects some of the enthusiasm of the time. This is what he said:

“Permit me as an anthropologist to point out two facts that seem to be overlooked by those who write about corporal punishment. The first is, the worse the criminal the less sensitive he is to pain, the correlation between the bluntness to moral feelings and those of the bodily sensations being very marked. The second relates to the connexion between the force of the blow and the pain it occasions, which do not vary at the same rate, but approximately, according to Weber’s law, four times as heavy a blow only producing about twice as much pain. In a Utopia the business of the Judge would be to confined to sentencing the criminal to so many units of pain in such and such a form, leaving it to anthropologists skilled in that branch of their science to make preliminary experiments and to work out tables to determine the amount of whipping or whatever it may be that would produce the desired results. Really these latter considerations might even now be made the subject of a solid scientific paper of no small interest, but they cannot be more that hinted at in a short letter like this, which has to be written in non-technical language” [25].

It is worth mentioning that, in a fully deterministic universe, it is not only the criminal who is predetermined. There is an ivory tower predestined for the technocrat, who is supposed to be preordained to be the good guy of the tale, and who lives off his numbers, charts, predictions, and high IQ.

An ancient tale sheds some light on the matters:

It is said that Zeno of Citum [26], the founder of stoicism, caught his slave stealing. As a punishment, Zeno beat the slave. The slave, who was aware of Zeno’s doctrines said, as he was being beaten:

—You shouldn’t punish me for stealing. Destiny, over which I have no control, has determined that I should steal.

Then Zeno answered:

—Destiny, over which I have no control either, has also determined that I have to beat you because of that.

By the late 1870s, Lombroso started a campaign to substitute Beccaria’s criminal law system. This group, made up of three eugenicists who took inspiration from Galton, went by the name “The Positive School of Penal Law”. It was composed of the Italian thinkers Cesare Lombroso, the sociologist Enrico Ferri (elected 11 times as a member of the Italian Parliament), and Raffaele Garofalo, an Italian senator.

The Positive School argued that several countries had been using Beccaria’s system for decades, and instead of attaining the goal of fully eradicating crime, there were plenty of criminals to be found within their territories. This, the Positive School claimed, was a clear sign of failure that could be attributed to an ineffective system. As if that wasn’t enough, Ferri, who had gotten access to then newly available statistical reports, said that the situation was getting worse, as some of those nations were showing a spike in criminality. This made the replacement of Beccaria’s system urgent.

According to the Positive School, a replacement needed to be elaborated, that was sustained, this time, not on legal abstractions but on scientific grounds.

One of the first things to dispose of was free will, a notion considered as alien to causality. Free will, a key concept within Beccaria’s framework, is understood as the basis for “moral responsibility”, that is, the idea that someone can be punished because they have the freedom to choose their actions, and as such, they should be responsible for the repercussions of their acts. Instead, the Positive School proposed “social responsibility”, the idea that society had the right to defend itself against aggressors. No one could damage society with impunity. This was seen as the source of the right for society to punish those who infringed against it [21].

In addition, Beccaria’s syllogistic legal code had to be struck down. Ferri’s slogan was “down with the syllogism” [27], the criminal justice system had to orbit around deciphering the psychology of the individual, his criminal type, and act accordingly.

Just as diseases affected individuals, crime, the Positive School rationalized, was a social malady [i] that needed to be treated [19]. Treatment had to be personalized to the individual, just like in medicine.

Garofalo, who coined the term “criminology”, also came up with the idea of using a score for “peligrosity” or “dangerousness” [27], which was supposed to be measured scientifically, to attempt to calculate how likely someone was to commit a crime. In the absence of free will, Garofalo argued, there was no need to wait for a crime to be committed. If someone’s “dangerousness” was too high, they had to be incarcerated before a crime took place.

Eventually, in order to corroborate Lombroso’s ideas, the comparison extended. It wasn’t only that criminals were similar to atavistic savages, they were similar to children. Garofalo explains:

“The Theory of Atavism. — Because of the marked resemblance between the typical criminal and the savage considered as a representative of prehistoric man, Lombroso held to the theory of atavism. Certain characteristics of prehistoric skulls of criminals confirmed him in this view. In addition, his psychological studies of infancy, —which reproduces in miniature the first stages of human development, — resulted in the discovery of many characteristics also observable in savages and criminals” [28].

This comparison to children follows from the logic of the biology of the time [j].

The “born criminals”, as conceived by Lombroso, were supposed to constitute around 33% of the criminal population. When dealing with these “monsters”, Garofalo was in favor of separation, forced labor, and the death penalty. Lombroso had argued in favor of the death penalty by saying [29] that, when someone was faced by a dangerous animal, the way to deal with it was by killing. Society should act in a similar fashion.

Garofalo regretted that, since the Beccarian system renounced determinism and a scientific outlook on crime, it seemed as if it was made with the clear purpose of aiding crime spread and multiply. The idea of trying to reach some “absolute ideal justice”, was simply unattainable and a mirage [28]. People do not agree on philosophy and moral values, but on science.

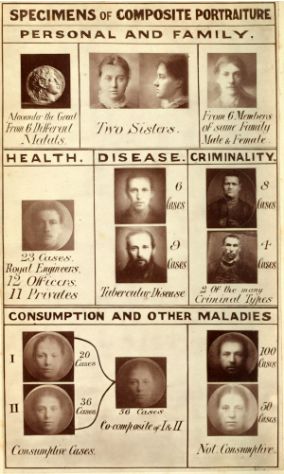

Lombroso [k], who started the movement, had spent a big amount of time studying the facial features of criminals, hoping that they would somehow be linked to crime. He thought to have found facial traits that corresponded to some criminals.

Similar trends were taking place in England.

Galton invented the composite photograph, in an attempt to try to link criminality with certain facial features, and published his method in Nature, in 1876, even though he failed at finding the patterns that he was originally searching for. He also pioneered the study of fingerprints, hoping to match different prints to different races. He failed as well, but he suggested that fingerprints could be helpful as evidence to identify criminals [30]. Karl Pearson, Galton’s apprentice and close ally in disseminating his work, studied the claims of the Positive School’s Research and responded.

Pearson and a few others affiliated with the University of London published The English Convict in 1913, after Galton’s death in 1911. They concluded, after examining data coming from 3,000 convicts that “there is not any significant relationship between crime and what are popularly believed to be its ‘causes’, and that crime is only to a trifling extent the product of social inequalities or adverse environment, and that there are no physical, mental, or moral characteristics peculiar to the inmates of English Prisons: that one of the principal determinants of crime is ‘mental defectiveness,’ and as this is a heritable condition, the genesis of crime must to this extent be influenced by heredity” [31].

Twenty-one years later, Karl Pearson showed up to a dinner party for his retirement. He was stepping down from his position as Francis Galton Chair of National Eugenics at University College London. There he delivered a speech, where he spoke with satisfaction, knowing the impact that he and his mentor had in the world. This is what he said about his career:

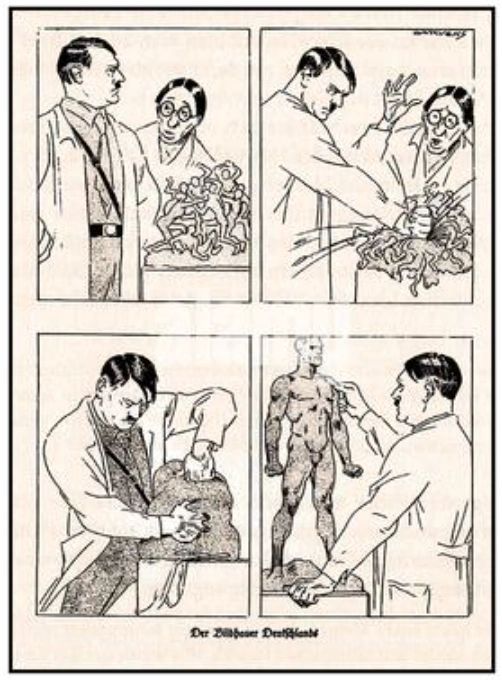

“The climax culminated in Galton’s preaching of Eugenics, and his foundation of the Eugenics Professorship. Did I say ‘culmination’? No, that lies rather in the future, perhaps with Reichskanzler Hitler and his proposals to regenerate the German people. In Germany a vast experiment is in hand, and some of you may live to see its results. If it fails it will not be for want of enthusiasm, but rather because the Germans are just starting the study of mathematical statistics in the modern sense!”

A year before, the National Socialist Party of Germany came to power, and Germany passed its Law for the Prevention of Genetically Diseased Offspring [32].

Part 7: The explosion of Galtonian thought worldwide

In the 1900s, psychological testing changed rapidly. Galton’s approach to the measuring of intelligence, explained in Hereditary Genius, consisted of reviewing the biographies of those whose excellence in a certain discipline, such as math, literature, philosophy, etc., had positioned them in high public esteem. Next, Galton did the tedious job of looking at the genealogical trees of these “geniuses”, compiling as much as he could of the biographies of their relatives. In a rather subjective way, Galton deemed who, among these relatives, were remarkable due to their accomplishments, then counted them up. This enabled him to statically estimate how common it was for an “eminent genius” to have relatives who were also highly “eminent” [3]. As flawed as his research methods were, it was considered groundbreaking at the time [2].

With this information in hand, he then proceeded to say that it was more common for a genius to have relatives who themselves were much smarter than for the average person. This proved, according to him, that intelligence was a biologically inheritable trait that ran through families. One can see how this kind of analysis made sense in the English society of the time, which had profoundly monarchical roots where pedigree depended on familial ties. While Galton was aware of the setbacks of his research, he thought that his efforts were sufficient to prove his point [3].

Despite Galton’s ambitions, his approach to the study of intelligence was impractical when it came to setting up the eugenics system he had envisioned at the societal level. His system wasn’t “scalable”; it wouldn’t be possible to study genealogical trees and biographical accounts in mass, because many people didn’t have such records to begin with, or, in case they had them, the records would be too subjective, unreliable, and difficult to handle. However, many saw the promise of overcoming these limitations in the standardized tests developed by Alfred Binet, which could be used to test large quantities of people at once [4]. Binet was impressed by Galton’s attempt to study individual psychological differences through standardized tests, so he adapted his method and supplemented it with observations on body type, handwriting, and other characteristics. In the early 1900s, he and Theodore Simone developed scales to measure the intelligence of children [33]. Although Binet believed that intelligence was malleable [34], and his test was merely designed to identify students who needed special help in class, his test was later used by American psychologists with different purposes. Unknowingly, he set the basis for what became a zealousness over intelligence scores [4].

In 1906, Henry Goddard, one of the founders of American psychology [35], was hired by the Vineland Training School in New Jersey, a school for those with “imbecility”, which was the term at the time for those deemed to have low intelligence. Eugenicists were worried that the population of “imbeciles” was increasing through breeding. As they reproduced and multiplied uncontrollably, the government would have to devote ever more taxation resources for their care, and it wouldn’t be feasible, from an economic standpoint, to continue to do so. Goddard was hired to find a way to quell the tide. At the time, doctors usually diagnosed “imbecility” through intuition; however, Goddard, a eugenicist himself, used Binet’s test to try to study it scientifically [4].

Goddard was particularly concerned about the “moron”, someone whose intelligence was somewhat below normal, but not to the point of making it so obvious that they could be detected merely by their looks. It was thought that those whose lack of intelligence was extreme and evident tended not to reproduce, which solved the eugenicist problem in the long run. On the other hand, the moron, Goddard argued, ran amok reproducing without any restrictions, lowering the intelligence of the whole population [36]. This blurry line between the moron and those of normal intelligence required a tool that would show who belonged to what group, in an attempt to gain control over their reproduction. IQ testing was seen as that tool.

But Goddard did not only think that people of lower intelligence degraded the quality of the population, he thought that they were closely linked to criminality [35]. Goddard was familiar with both Galton [l] and Lombroso [36], and became one of the fervent proponents of the usage of intelligence testing in the United States. Goddard even got to the point of asserting that IQ was a measure of how “human” someone is [35]. He was one of the many eugenicists in the United States who advocated for sterilization of the biologically unfit, segregation and social exclusion, and the curtailing of immigration [4][36].

At the beginning of the 20th century, eugenics were gaining notoriety, and became widely accepted in academic circles, including Harvard, one of the institutions where eugenics proliferated [37].

Charles Davenport, a zoology professor at Harvard University from 1892 to 1899, and a supporter of Galton, was the founder of the U.S Eugenics Records Office in 1910 in Cold Spring Harbor, New York. In fact, Davenport had met Francis Galton personally. The U.S. Eugenics Records Office had the purpose of obtaining hereditary information on American families. Davenport constantly advocated for eugenics on the Harvard campus, gathering students’ attention to the field. In a letter that Davenport [m] sent to Galton, for the celebration of Galton’s birthday at Harvard, Davenport mentioned “[my] arms ached for days in consequence of having to transport your books and serials containing your briefer articles from the libraries [38]”.

In August 1912, a year after Francis Galton’s death, Harvard president emeritus Charles William Eliot addressed the Harvard Club of San Francisco to discuss the importance of keeping a nation genetically pure [37].

Harvard Magazine itself claims that espousing eugenics beliefs did not create problems for Eliot, as this was “well within the intellectual mainstreams of the University. Harvard administrators, faculty members, and alumni were at the forefront of American eugenics– founding eugenics organizations, writing academic and popular eugenics articles, and lobbying government to enact eugenics laws. And for many years, scarcely any significant Harvard voices, if any at all, were raised against it. Harvard’s role in the movement was in many ways not surprising. Eugenics attracted considerable support from progressives, reformers, and educated elites as a way of using science to make a better world. Harvard was hardly the only university that was home to prominent eugenicists… But in part because of its overall prominence and influence on society, and in part because of its sheer enthusiasm, Harvard was more central to American eugenics than any other university. Harvard has, with some justification, been called the “brain trust” of twentieth-century eugenics…”

Similarly, at Yale University, in the late 19th and early 20th century, the sociologist William Graham Sumner [39] was advocating for eugenics and social Darwinism, in the context of capitalist policies. Sumner was extremely influential, and held the first professorship in sociology in the United States. He claimed:

“Nature is entirely neutral; she submits to him who most energetically and resolutely assails her. She grants her rewards to the fittest, therefore, without regard to other considerations of any kind. […] If we do not like it, and if we try to amend it, there is only one way in which we can do it. We can take from the better and give to the worse. We can deflect the penalties of those who have done ill and throw them on those who have done better. We can take the rewards from those who have done better and give them to those who have done worse. We shall thus lessen the inequalities. We shall favor the survival of the unfittest, and we shall accomplish this by destroying liberty. Let it be understood that we cannot go outside of this alternative; liberty, inequality, survival of the fittest; not-liberty, equality, survival of the unfittest. The former carries society forward and favors all its best members; the latter carries society downwards and favors all its worst members.”

This immense tide of eugenics thinking had huge political ramifications. Sterilization laws of the “biologically unfit” began in the United States in 1907, the first eugenics law passed in the world [40]. Immigration to the United States was greatly restricted in the 1920s, with immigrants given IQ tests when they attempted to enter the country [4]. And US racial school segregation was prolonged, officially, until 1954 [41], partially due to eugenicist intellectuals [4].

By the 1920s and 30s, the Germans had embraced eugenics and Lombrosian thought in their approach to crime. The postulates of the Positive School of Penal Law altered Italian policies in a comparatively mild way (An important distinction between Italy and Germany was that Italy was a predominantly Catholic country, and Catholics rejected eugenics). However, Germany took the Lombrosian outlook, embraced a fully biological perspective in regards to their understanding of crime, and consequently saw eugenics as the optimal way to deal with criminality [42].

Criminal-biologists became the dominant intellectual force in charge of analyzing crime in Nazi Germany [n]. Within this context, there were Nazis compiling data in German prisons for scientific studies; in one of them, led by the Nazi physician Robert Ritter in more than 70 German prisons, information was compiled with the purposes of: “First, through the criminal-biological examinations[,] Nazi criminologists hoped to be able to genetically classify every prisoner in Germany. Second, they planned to make the results of the examinations useful at sentencing by creating a kind of genetic presentence report upon which judges could base their decisions. Third, the examination results would be useful in identifying those criminals who should be sterilised. And fourth, […] to compile a universal archive of genetic information that would enable [them] to predict who would become criminals so that they could be immobilised before they started committing crimes” [42]. They hoped to create a system that resembled Garofalo’s system of diagnosing someone’s “peligrosity”, in opposition to Beccaria’s free will.

However, a key point has to be examined with particular attention in order to understand the historical context explored so far. Decades prior to the creation of any of these worldwide eugenic laws and policies of the 20th century, in 1869, when Galton formulated his views in Hereditary Genius, he argued that, since different races have different heights on average, it follows that different races have, on average, different levels of intelligence. Therefore, if the smartest race, (conveniently he argued that the group that he belonged to, the Northern Europeans were the most intelligent) mixed with a race of lower average intelligence, the result would be a collective regression towards intellectual mediocrity. This called for extreme precaution in reproductive matters, since lack of reproductive control would lead to mass degradation of the smartest group.

Francis Galton had proposed in his writings that there were also those who statistically displayed extraordinary intelligence in different racial groups. In addition, under his set of assumptions, it is clear that any race could be chosen to be engineered in order to increase their intelligence; he estimated that the Greeks during their most prosperous times were smarter than the British society. But Galton’s conception of race wasn’t one-dimensional. He understood that race was somewhat of an imperfect, arbitrary category, since he thought that “races” are the result of the historical mixture of different groups, due to war, commerce, migration, etc. Therefore, where one race begins and the other ends isn’t clear. Race, for Galton and many other eugenicists, was merely seen as a heuristic for intelligence. Therefore, race was accessory, secondary to something with even more relevance within the Galtonian system, that is, intelligence. After all, he had written a book whose full title was “Hereditary Genius: An Inquiry Into Its Laws and Consequences”, a book where race served as guidelines for his intelligence-enhancement oriented policies, or, to put it in different words, race marked the limits for his open lab for artificial selection based on intelligence.

It is within this mindset that those who are considered not intelligent are seen as insufficient and human waste for the social organism. This would explain why it wasn’t only those who belonged to other races who became targets of aggressive policies; the feeble-minded, the criminal, the homeless, the mentally ill, and the weak and disabled, were increasingly seen as unintelligent, counterproductive and wasteful. They were supposed to be discarded as well, despite being members of the same race. Galton imagined that the discovery of evolution marks a new epoch, a pinnacle moment where humans can finally claim control over what in the past has been a cruel, wasteful, and violent evolutionary process that was plagued by randomness and lack of conscious guidance, but that could finally be tamed, and redirected, thanks to the discovery of artificial selection [3].

In 1927, the Supreme Court of the United States decided over the case Buck vs. Bell, and upheld the decision to forcibly sterilize a White foster child, Carrie Buck, after her foster parents deemed her “feeble-minded” [43], even though she was an average student [44]. Up to the 1970s, the United States conducted about 70,000 forced sterilizations [45], Sweden about 60,000 [46], Norway about 40,000 [47], Denmark about 6,000 [47], and Canada about 3,000 [48], with it still actively occurring and legal in many countries, such as China and India [49].

After the court case Buck vs. Bell, Germany followed suit and sterilized about 600,000 people [], often “imbeciles” deemed unfit to breed. By 1933, the Nazis had enacted the Law for Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring or Sterilization Law, “authorising compulsory sterilisation of people said to be afflicted with congenital epilepsy, feeble-mindedness, mental diseases such as schizophrenia, alcoholism, and other supposedly heritable afflictions. This law, [was] inspired by US eugenics research and modeled on similar US legislation […] Hitler himself had wanted to include criminals under the Sterilization Act, but officials in the Ministry of Justice, in an incident illustrating their commitment to science, resisted the Führer on the grounds that they were not yet sure of the criteria for sorting hereditary from nonhereditary offenders” [42]. During the subsequent Nazi T4 program, initiated in 1939, 200,000 people were killed [4], with the criteria for murder largely economic; if someone was deemed medically unfit to work, they were called “burdensome lives” and “useless eaters”. Its goal was to “kill incurably ill, physically or mentally disabled, emotionally distraught, and elderly people” [50].

Although many people, today, associate eugenics principally with the Holocaust, intellectuals in the United States were arguing for gas chambers to be built to kill its vulnerable members decades before [4]. Germany itself claimed it was directly inspired by the US [51], as many US institutions, such as the American Psychological Association [52], Planned Parenthood [53], and universities including Harvard [37], were heavily involved in eugenics. Henry Goddard stated in 1913, “For the low-grade idiot, the loathsome unfortunate that may be seen in our institutions, some have proposed the lethal chamber” [36]. A reporter goes as far as claiming that the American eugenicists were “envious” of the progress German eugenicists were accomplishing, with one eugenicist expressing his concern as, “The Germans are beating us at our own game” [54].

Millions died as the Holocaust unfolded, beginning in 1941.

As a swing of a pendulum, the collapse of Nazism marked a return towards humanism, spearheaded by the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948 by the United Nations. This document drew inspiration from the philosophical, political, and judicial ideals of the Enlightenment, particularly from the French 1789 On the Rights of Man and the Citizen. Beccaria played an important role in the creation of both documents.

Ever since World War II, treaties aimed at granting Human Rights shaped international law, while signatories committed to make Human Rights a central point in their inner judicial affairs. Inalienable rights were supposed to be granted to everyone. The first article of this Declaration reads: “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. They are endowed with reason and conscience and should act towards one another in a spirit of brotherhood.” The Declaration recognized everyone as equal in front of the law, and rejected discrimination and torture.

With major wars taking place in the 40s, many fled Europe. In the aftermath of WWII, the rights of refugees and asylum seekers became a concern for international law, and migratory countermeasures to regulations inspired by eugenics were created, granting rights to those who were forced out of their countries and displaced.

While initially, the legal rights granted by the Enlightenment were given only to small privileged groups, as political fights took place in order to increase the scope of these rights, humanism’s range grew in significant ways, embracing different sectors of society that had been historically marginalized.

However, even though eugenics fell out of favor after the Holocaust, Galton’s specter is to be found lurking in the 21st century. Is, as many fear, the pendulum moving the other way?

Notes:

[a] Darwin says: “The great power of this principle of selection is not hypothetical. It is certain that several of our eminent breeders have, even within a single lifetime, modified to a large extent some breeds of cattle and sheep. […] Breeders habitually speak of an animal’s organisation as something quite plastic, which they can model almost as they please. If I had space I could quote numerous passages to this effect from highly competent authorities.” Then he continues, “That most skilful breeder, Sir John Sebright, used to say, with respect to pigeons, that ‘he would produce any given feather in three years, but it would take him six years to obtain head and beak” [1].

[b] The reader is suggested to look at the wikipedia page “fancy pigeons”. It provides a collection of images of these unusual birds. The drawings shown here can be found in the book “Fancy pigeons: containing full directions for their breeding and management, with descriptions of every known variety, and all other information of interest or use to pigeon fanciers.” It was written by James C. Lyell 1887. (Lyell, 1887) The author considered the topic worthy of more than 400 pages.

[c] Galton starts Hereditary Genius without rodeos saying: “I propose to show in this book that a man’s natural abilities are derived by inheritance, under exactly the same limitations as are the form and physical features of the whole organic world. Consequently, as it is easy, notwithstanding those limitations, to obtain by careful selection a permanent breed of dogs or horses gifted with peculiar powers of running, or of doing anything else, so it would be quite practicable to produce a highly gifted race of men by judicious marriages during several consecutive generations” [3].

[d] Galton writes in Essays in Eugenics “The possibility of improving the race of a nation depends on the power of increasing the productivity of the best stock. This is far more important than that of repressing the productivity of the worst. They both raise the average, the latter by reducing the undesirables, the former by increasing those who will become the lights of the nation. It is therefore all important to prove that favour to selected individuals might so increase their productivity as to warrant the expenditure in money and care that would be necessitated.” Then, referring to England: “To no nation is a high human breed more necessary than to our own, for we plant our stock all over the world and lay the foundation of the dispositions and capacities of future millions of the human race” [6].

[e] There is a section of Essays in Eugenics dedicated to marriage restrictions. Galton looks at the caste system in India. He says that new mariage restrictions should be held in accordance with the precepts of eugenics [6].

[f] Galton often proposes the replacement of those who are subjected to religious celibacy, in his perspective, those whose intelligence is inferior should be the ones that are incentivized by society to abstain from sexual activities. In order for these ideas to expand, he asserts the need for a new religion that has eugenics at its core [6].

[g] Beccaria puts it: “They err, therefore, who imagine that a crime is greater, or less, according to the intention of the person by whom it is committed; for this will depend on the actual impression of objects on the senses, and on the previous disposition of the mind; both which will vary in different persons, and even in the same person at different times, according to the succession of ideas, passions, and circumstances. Upon that system, it would be necessary to form, not only a particular code for every individual, but a new penal law for every crime. Men, often with the best intention, do the greatest injury to society, and with the worst, do it the most essential services […]” then he says: “[Who can] pretend to punish for the Almighty, who is himself all sufficient; who cannot receive impressions of pleasure or pain, and who alone, of all other beings, acts without being acted upon?” [55]

[h] Beccaria wrote his book An Essay on Crime and Punishment when he was 26 years old. Manzanera explains that the book caused “one of the biggest intellectual commotions ever seen in the history of humanity” . Then he says about his text “a work so valuable that can be considered the founding piece of Criminal Law in a modern sense” [21].

[i] Ferri writes: “Not until the experimental and scientific method shall look for the causes of that dangerous malady, which we call crime, in the physical and psychic organism, and in the family and the environment, of the criminal, will justice guided by science discard the sword which now descends bloody upon those poor fellow-beings who have fallen victims to crime, and become a clinical function, whose prime object shall be to remove or lessen in society and individuals the causes which incite to crime. Then alone will justice refrain from wreaking vengeance, after a crime has been committed, with the shame of an execution or the absurdity of solitary confinement” [19].

[j] Garofalo provides some more insights into the ways in which the role of children was understood by the Positive School, and what the logic behind their claims was when he references Haeckle later in his book: “Almost all children during the first years of their life seem destitute of moral sense. Their cruelty to animals is well known, as is also their propensity to seize what belongs to others. They are thoroughly egotistic, and in seeking to satisfy their desires, they are not in the slightest degree concerned with what they make others suffer. In most cases all this changes with the approach of adolescence. But can it be said that this psychological transformation is the effect of education?

Are we not rather to see in it a simple phenomenon of organic evolution, similar to the embryogenic evolution by which the fetus passes through the different stages of animal life, beginning with the most rudimentary and ending with that of man? It has been said that the evolution of the individual is an epitome of that of the species. Thus in the psychic organism the instincts which primarily appeared must have been those of the animal, next must have come the ultra-egotistic sentiments, then in succession the ego-altruistic sentiments as acquired first by the race, secondly by the family, and lastly by the parents of the child. The jusxtapositions of instincts and sentiments thus arising would be due not to education or to the influence of the immediate environment, but solely to heredity. ‘The conscience’ says Espinas, ‘grows in the same manner as the organism and parallel to it…” [28]

[k] Curiously, at some point Lombroso got interested in the study of the paranormal. Manzanera says about it: “Already since 1891, he was in contact with Eusapia Paladino, a famous medium, who in 1901 made him “see” his mother. This made him dedicate himself to spiritual experimentation and to write “Ricerche sui Fenomeni Ipnotice e Spiritici” [21].

[l] The reader might be interested in reading an article published in The New York Times, in march of 1885, it is entitled Improvement in cats. This is what it said:

“Mr. Francis Galton is one of the most ingenious and yet useless scientific persons now living. He is continually making some new discovery, but his discoveries are of the kind that benefit nobody. It is sad to see so much real ability as Mr. Galton unquestionably possesses frittered away in science. Were he to give his attention to something useful -whist for example- he might make himself a public benefactor instead of a mere object of curiosity.

He has latterly been trying to devise ways for the improvement of cats. No one will deny that this is a field in which great good might be done. The cat has not been improved within historic times. The cat of to-day is the identical animal that the Egyptians worshiped. She is just as objectionable as she was six thousand years ago, and no one has hitherto made any attempt to place an improved style of cat on the market.

Now, what does Mr. Galton do when he sets out to improve the cat? Does he attempt to improve the cat’s voice and method of singing, so that it will be possible for people to sleep at night in a community where cats thrive? Has he thought of substituting soft and innocuous paws for the armed and deadly paws now in use? Has he dreamed of so modifying the cat’s teeth that she can be accidentally stepped on in a dark room without subjecting the innocent aggressor to a lacerating bite that is sure to be followed by hydrophobia or lockjaw? He has done none of these things, and his whole energies have been concentrated on a plan to make cats totally deaf.

Mr. Galton has found that deaf cats are by no means uncommon. Indeed, nearly all the white cats with pink eyes are congenitally deaf. Mr. Galton informs the world that by careful breeding a race of deaf cats can be produced and in time made to take the place of other cats. This is the sole improvement in cats that he has at present thought of, and the fact shows us just what an impracticable and useless person Mr. Galton is.

There is no possible advantage in owning a deaf cat. The animal would sing, fight, scratch, and bite as vigorously as a cat in the full possession of her hearing. On the other hand, her want of hearing would make her positively objectionable. It would be useless and exasperating to request such a cat to “scat,” for she would pay no attention to a request that she could not hear. Boots and things would have to be thrown at her whenever it was desired to attract her attention, and it would be impossible to call her –no matter what endearing and flattering terms might be used– in case her presence was desired. While she might be induced to watch a mouse hole in case it were shown to her, she could not have her faculties stimulated by hearing mice gnawing or squeaking in the wall, and half a dozen rats might run over the floor when her back was turned without the least danger that she would notice them. For these reasons there is and can be no demand whatever for deaf cats, and yet deafness is Mr. Galton’s idea of the chief improvement that ought to be put upon cats.

Why could not the man see that what the world wants is a dumb variety of cat. Such an animal would be a blessing unalloyed except with claws and teeth. In the night her value would be beyond price. Hundreds of dumb cats might assemble on the back fence and spend the whole night in argument, but not a single sleeper would be disturbed. The keeneared watcher might occasionally hear the tearing of fur, and now and then a cat would drop from the fence into a hotbed and break a little glass, but the hideous caterwauling that in many parts of this city renders sleep almost an impossibility would be unknown. It is now now a common practice for a cat who has been shut out of the house at night to sit on the front step and mew until life becomes a burden to everybody within the radius of a quarter of a mile; for a cat has absolutely no consideration for the nerves of other people, and is a mere mass of compressed and consolidated selfishness. But no matter how much a dumb cat might want to get into the house at night she could not mention it, and she would be obliged to wait quietly and decently until morning.

If Mr. Galton would turn his attention to the invention of dumb cats he would do something of value for the human race. There is little doubt that by a trifling surgical operation on a cat’s throat dumbness might be secured. Cats rendered dumb by artificial means would in turn produce a race of kittens congenitally dumb, and as a result the average longevity of man be increased. Think for a moment what this world would be were the voice of the cat never again to be heard! Think of the hours of quiet sleep that we should have; the healthy condition of our nerves and the improvement of our morals that would follow the cessation of caterwauling! And then think for a moment on the stupendous stupidity of the scientific person who can think of no way of improving cats except that of making them deaf!”

[m] But Davenport wasn’t merely getting correspondence from Galton, he received an enthusiastic letter by Theodore Roosevelt, who acknowledged his work on eugenics. It can be found in the archives of the American philosophical society: https://diglib.amphilsoc.org/islandora/object/graphics%3A1487

[n] Dr. Robert Yerkes, a Yale Professor, who was also profoundly influenced by Galton, and who played an important role in the implementation of his doctrines on an international level, and of whom we’ll speak in the subsequent part of this text, says in an article for the New York Times, in the year 1941, entitled Would ‘Conscript’ Our Psychologists Dr. Yerkes Tells Philosophers This Preparation Is Vital to Offset Nazi Methods, how the Nazis are taking the lead in psychological warfare and psychological engineering. He claims the United States is “Psychologically Illprepared” to meet the challenges of the war, and claims that the success of the Germans is due to their “psycho-technology”. In previous years he had been a head of IQ testing in the military of the United States, testing hundreds of thousands.

[o] According to Manzanera, when Beccaria’s writings became an international success, his friends accused him of being unoriginal, and of merely writing ideas that were “already on the air”, and then broke apart from him. It is probably the case that Beccaria was compiling these ideas. However, Manzanera wonders if anyone can be original anyways? [21]

References

[1] Darwin, C. (2009). The origin of species: By means of natural selection, or, the preservation of favored races in the struggle for life. Penguin classics.

[2] Brookes, M. (2004). Extreme measures: The dark visions and bright ideas of Francis Galton. Bloomsbury : Distributed to the trade by Holtzbrinck.

[3] Galton, F. (2012). Hereditary genius: An inquiry into its laws and consequences. Barnes & Noble Digital Library.

[4] Zimmer, C. (2019). She has her mother’s laugh: The powers, perversions, and potential of heredity. Dutton, an imprint of Penguin Random House LLC.